If Uganda had built a proper advertising pipeline, this story would be very boring. There would be brochures in Senior Six career offices defining “account management.” Parents would nod proudly when their children said, “I want to be a copywriter.” Makerere would have a Faculty of Integrated Communications and Creative Strategy. There’d be a predictable path: degree, internship, junior role, promotion. Instead, the people who built this industry came in through side doors. One thought “copywriting” was about copyright law. Another was meant to be a pharmacist. One was headed for law before veering into fine art. Another walked into…

MADMEN, DREAMERS, AND DEAL-MAKERS – The Accidental Admen: How Uganda’s Creative Giants Found Their Way into the Industry Uganda’s advertising giants didn’t follow a career ladder; there wasn’t one. They arrived by phone calls, rugby chats, cricket links, art detours, even a flip-flop epiphany, thinking they were headed for law, pharmacy, IT, or teaching. Advertising found them through side doors, then held them through freedom, craft, and lessons. Out of improvisation, they built agencies, systems, and standards that now define the industry, and open it to the next beautiful accident.

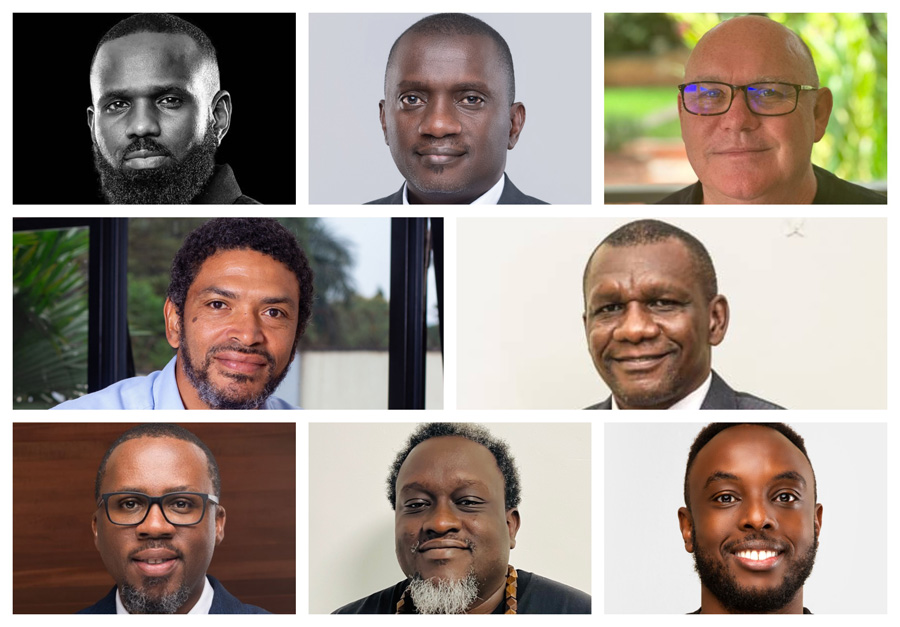

A photo collage of Jeffrey Amani, Adris Kamuli, David Case, Peter Magona, Daniel Ligyalingi, Rommel Jasi, Alemu Emuron, and Joshua Kamugabirwe. Uganda’s ad industry was built by “accidentals” who wandered in through cricket pitches, rugby chats, art schools, and random interviews. With no clear pipeline, they learned by doing, then became founders, mentors, and standards-setters—turning side doors into institutions and asking how to keep luck alive, but kinder, for others today.