Uganda’s oil ambitions face a critical stress test at the Kasuruban oil block.

By handing it to Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC), government signaled that national control must sit at the heart of its petroleum future.

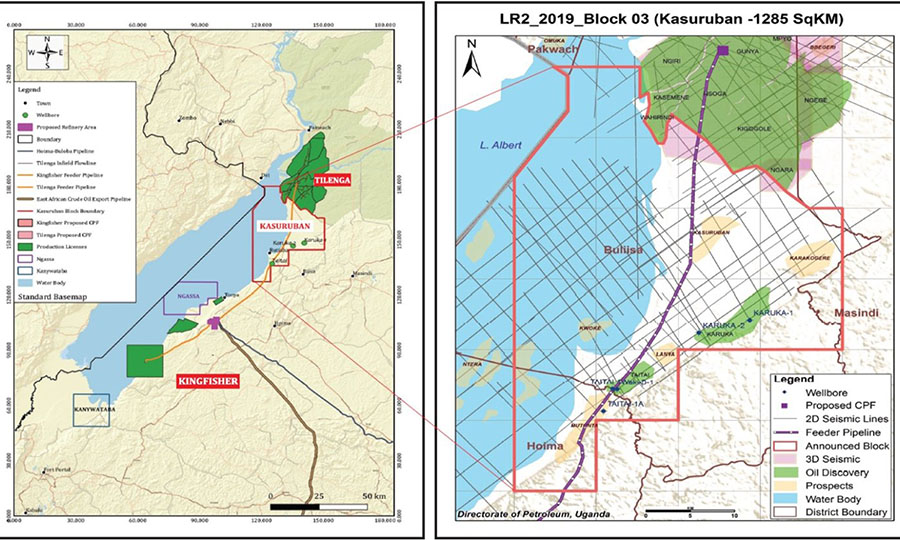

With a total area of 1,285 square kilometers spread across Buliisa, Hoima, and Masindi districts, Kasuruban is Uganda’s largest oil block by land area.

But control comes with obligations. Having moved into the second phase of its license, UNOC is now expected to reprocess seismic data and drill at least one exploratory well.

It is an expensive step that could cement Uganda’s sovereignty in the upstream, or expose taxpayers to risks they never bargained for.

On paper, this is a landmark moment: the first time Uganda’s commercial arm takes the lead in upstream exploration.

In reality, it exposes a classic dilemma that every resource-rich but capital-constrained country faces.

Can Uganda build national control over its petroleum endowment without transferring too much financial risk onto taxpayers?

Kasuruban magnifies this tension. The Albertine Graben is geologically prolific.

87% of wells drilled to date have struck oil, a success rate far above the global average of approximately 30%, according to geological data from the Petroleum Authority of Uganda.

That tilts the odds in UNOC’s favour. Yet oil exploration remains probabilistic, not guaranteed.

And with the global energy system undergoing structural change — majors tightening capital discipline, banks scrutinizing hydrocarbon lending, and governments shifting incentives toward renewables — Uganda is entering the upstream game at a time when attracting capital is more complex than geology alone.

The promise and the peril

With an estimated 6.5 billion barrels of oil in place across the basin, the probability of commercially viable discoveries at Kasuruban is high.

For UNOC, success would be transformative. It would mark the company’s evolution from a shareholder in Tilenga, Kingfisher, and the EACOP pipeline — roles that make it more of a rent collector — into a bona fide upstream operator with technical credibility and operational control.

In industry terms, it would move UNOC up the value chain, shifting from a passive equity position into a more strategic operator role.

That comes with prestige, bargaining power, and the potential for greater rent capture.

But geology is only half the story. Drilling is both capital-intensive and uncertain.

A single exploration well in Uganda costs around $40 million, many energy economists note.

The figure reflects both logistical challenges and limited economies of scale compared to frontier basins backed by majors.

In global terms, that is modest, but in the context of Uganda’s fiscal position – where debt servicing already consumes close to 30% of government revenue — such sums are significant.

An unsuccessful well would not just be a geological disappointment; it would represent foregone classrooms, hospitals, or infrastructure projects.

That makes the downside far more acute. A dry hole would not only be a technical setback; it would translate into real fiscal pain.

It would be at a time when debt service already consumes nearly a third of government revenue.

It would also carry political costs. Citizens are acutely aware that every dollar spent on exploration is a dollar not spent on health, education, or infrastructure.

As Peter Muliisa, UNOC’s chief legal officer, put it: “Getting taxes and we sink it in a well and find no oil, is a risk we cannot swallow as of now.”

This is the central dilemma. Upstream participation promises sovereignty, value capture, and national capability.

Yet exploration remains inherently speculative – the kind of high-risk, high-reward gamble that sovereign balance sheets are ill-suited to carry alone.

For a state-backed company like UNOC, every misstep risks becoming a public liability.

Unlike a supermajor such as TotalEnergies or ExxonMobil, it does not have a diversified portfolio to spread the risk.

Its “balance sheet” is ultimately the Treasury.

This is why upstream oil exploration is not just a technical or geological undertaking — it is a financial wager.

Sovereign participation promises greater value capture.

Governments that own a larger working interest in their oil blocks stand to retain a greater share of future profits.

They reduce exposure to aggressive cost recovery claims, and develop local technical expertise.

But sovereignty has a cost. Unless government can attract a financially robust partner, taxpayers become the de facto underwriter of drilling uncertainty.

Why oil majors are sitting out

Notably, neither TotalEnergies nor CNOOC — the two firms already leading Uganda’s upstream developments — pitched to partner with UNOC.

CNOOC has instead doubled down on its $2 billion Kingfisher development, which is on track to deliver first oil next year.

It is also simultaneously eyeing the larger Pelican and Crane block that UNOC beat it to in the 2022 licensing round.

TotalEnergies, meanwhile, appears focused on de-risking its Tilenga and EACOP commitments at a time when the capital cycle for oil is tightening.

Their absence is telling. It underlines the new discipline that defines global upstream investment.

Gone are the days when international majors chased every frontier opportunity for reserves replacement.

Today, capital allocation is shaped by three pressures. Shareholder demand dividends over new spending.

There is regulatory and reputational pressures around ESG, and a preference for projects that can deliver barrels quickly with lower above-ground risk.

Uganda scores high on geological promise, but low on timelines and capital efficiency.

With first oil production pushed into the late 2020s, and logistical and financing bottlenecks still unresolved, the basin appears strategic but marginal for major oil companies.

This is the structural challenge for frontier producers like Uganda.

National oil companies tend to view barrels in place as assets to be monetized at almost any cost.

They underpin state revenues, sovereignty, and industrial policy.

International oil companies, however, see them as one more entry in a global portfolio that must compete for scarce capital.

That asymmetry explains why even in a basin with an 87% exploration success rate, Uganda cannot automatically count on the majors.

The economics of risk-sharing

This leaves UNOC reliant on attracting a second-tier or niche upstream player.

Most likely a private equity-backed independent or a smaller national oil company from Asia or the Middle East.

One that is willing to shoulder exploration risk in exchange for a foothold in a proven but still underdeveloped basin.

The structure of that joint venture will be decisive.

If UNOC insists on holding a large stake without bringing proportional financing, the Treasury remains indirectly exposed to cash calls.

Yet if it concedes too much equity, Uganda risks diluting the very sovereignty and value capture it set out to protect.

The economics of oil partnerships hinge less on geology than on contract design.

Cost-recovery clauses, carry arrangements, and production-sharing splits determine who ultimately pays for dry wells.

It determines who recoups investments first, and how much fiscal take accrues to the state over the project life.

For a frontier producer like Uganda, the margin for error is thin.

One poorly structured deal can lock government into obligations that last for decades.

A possible middle ground is to ring-fence UNOC’s contribution to technical oversight and regulatory leverage.

But allow the partner to bear most of the capital burden.

But achieving that balance requires deft negotiation, especially in an environment where international investors demand competitive terms and clear exit options.

Strategic timing

The global oil outlook adds another layer of complexity. Analysts at Wood Mackenzie stress that while oil demand is not vanishing overnight, the investment landscape has fundamentally changed.

Volatile prices, rising interest rates, and ESG-driven divestments mean that capital for long-cycle upstream projects is harder to secure.

Capital is more expensive to hold and this is colliding with Uganda’s target for first oil by next year.

For UNOC, the decision to double down on Kasuruban carries a binary risk.

If exploration proves successful and timelines hold, Uganda could graduate from being a passive equity holder.

The country would graduate into an upstream operator, securing greater control over resource rents.

But if the wells disappoint, Uganda risks becoming a late entrant pouring scarce capital into a sector where global finance is steadily retreating from.

Timing, in oil as in markets, can be the difference between sovereignty and stranded assets.

Beyond geology: sovereignty versus liability

Kasuruban is more than a block; it is a litmus test for Uganda’s brand of resource nationalism.

By reserving it for UNOC, government signaled that state control is the anchor of its oil future. But in oil, control without capital is fragile.

If UNOC can marry technical execution with a credible partner, Kasuruban could showcase a model where Uganda builds upstream capacity while limiting fiscal exposure.

That would be a rare success in a region where national oil companies either overextend financially or become junior partners in their own basins.

But if the wells turn out dry, or if joint venture negotiations tilt too far against the state, Kasuruban risks morphing into an expensive reminder.

The strategic question, therefore, is not simply whether Kasuruban holds oil— the Albertine has already proven itself.

The question is whether Uganda can design a partnership structure that gives UNOC meaningful control and upside. A partnership that insulates public finances from the volatility of exploration.

That balancing act — between sovereignty and liability — is where the real economics of Kasuruban will be tested.

Modernising General Insurance: SanlamAllianz CEO Ruth Namuli on Building Uganda’s Insurance Powerhouse with Trust, Innovation, and Scale

Modernising General Insurance: SanlamAllianz CEO Ruth Namuli on Building Uganda’s Insurance Powerhouse with Trust, Innovation, and Scale