Ahead of a historic milestone for Uganda’s health and education sectors, The CEO Magazine sat down with Aga Khan University Hospital CEO Rashid Khalani. Last week, Kampala hosted the inauguration of the Aga Khan University Centre and the ground-breaking ceremony for the upcoming Aga Khan University Teaching Hospital in Nakawa – projects set to transform medical training and healthcare delivery in the country. In an exclusive conversation, Rashid Khalani shared insights on the vision, impact, and opportunities these developments will bring. What are the most pressing health challenges facing Africa today? There are three interlinked challenges. First is human capacity….

Quality First: How Aga Khan University Hospital Is Strenthening Uganda’s Healthcare Last week, Uganda witnessed two landmark events—the inauguration of the Aga Khan University Centre and the ground-breaking of the Aga Khan University Teaching Hospital in Nakawa. Together, these projects promise to transform medical training and healthcare delivery in Uganda. Against this historic backdrop for the country’s health and education sectors, CEO East Africa Magazine sat down with Aga Khan University Hospital CEO Rashid Khalani, who shared his vision, the impact these initiatives will have, and the opportunities they open for Uganda and the wider region.

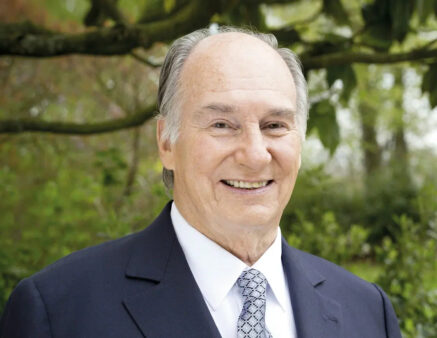

Rashid Khalani, CEO of Aga Khan University Hospital, outlines a bold vision to transform Uganda’s healthcare through world-class quality, specialist training, and expanded access.