As one drives into Hoima City, the urban heart of Uganda’s oil dreams, it quickly becomes clear that this is no ordinary town.

The city has become a magnet for ambition, its heartbeat quickened by oil fortunes that promise to rewrite the region’s history.

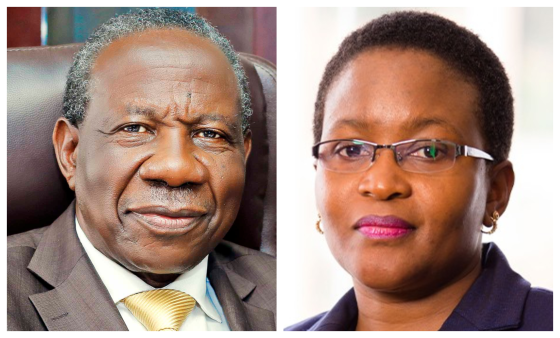

New hotels now rise where bushes once stood. Few names carry as much weight as Kabagambe Kaliisa, a respected geologist who spent decades in the Ministry of Energy before becoming the President’s Advisor on Oil and Gas.

In Hoima, his influence stretches beyond policy. His Miika Eco Resort Hotel, a haven for visiting oil executives, hums with quiet luxury.

He also runs Albertine Water, a growing bottled-water brand, among other ventures tied to the oil boom.

At night, Hoima’s skyline glows with neon lights from new clubs and bars. Other familiar names, such as former Deputy Prime Minister Muganwa Kajura, have family businesses woven into the city’s transformation.

A few kilometres outside the city, the Hoima City Stadium, financed by the Petroleum Fund, rises from red earth like a monument to new beginnings.

The Kabalega International Airport stretches across the savannah built to handle cargo planes that will ferry machinery for the refinery’s construction.

Hoima’s story is proof that Uganda’s oil dream has moved from speculation to substance, even if that substance remains unevenly distributed across the region.

The long road to the promise

When Uganda discovered 1.4 billion commercially recoverable barrels of oil in 2006, the nation erupted in hope.

The “black gold” beneath the Albertine Graben was seen as a passport to industrialisation, self-reliance, and energy security.

Nearly two decades later, that promise remains partly unfulfilled, delayed by bureaucracy, politics, and the complexities of mega-project execution.

Government projections now point to June 2026 as the long-awaited “first oil” moment.

Officials defend the timeline with cautious optimism, though the oil journey has been marked by shifting targets and faltering partnerships.

The refinery story began in 2010, when British firm Foster Wheeler completed a feasibility study recommending a 60,000-barrel-per-day refinery.

But financing and location politics loomed large.

In 2015, government selected a Russian consortium led by RT Global Resources as the preferred developer. Negotiations later collapsed amid disagreements over risk allocation, equity structure and mounting sanctions.

Between 2017 and 2020, the upstream sector reshuffled. Tullow Oil’s attempt to sell its Ugandan assets initially failed but finally closed in November 2020 at $575 million, leaving TotalEnergies and China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) as the dominant players.

In February 2022, Uganda signed the long-delayed Final Investment Decision (FID) for the Tilenga and Kingfisher projects, alongside the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP).

Spudding, or actual drilling, began in January 2023. By late 2024, the Petroleum Authority of Uganda reported Tilenga at 45% completion, Kingfisher at 58%, and more than 90% of the planned 420 wells drilled.

However, in June 2023, government terminated the refinery deal with the Albertine Graben Refinery Consortium (AGRC) after its financiers failed to deliver.

Two years later, on March 29, 2025, Uganda signed a new Implementation Agreement with Alpha MBM Investments LLC, a Dubai-based firm that took a 60% stake in the refinery, leaving 40% to Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC).

Meanwhile, work on the 1,443-kilometer EACOP pipeline accelerated. As Western banks bowed to activist pressure over environmental concerns, Uganda turned to Chinese banks, local lenders, and Gulf financiers to keep the USD 5 billion project alive.

By mid-2025, the first oil date had been quietly moved from 2025 to 2027, citing the need for sequenced infrastructure completion.

Critics argue Uganda’s oil timelines often align with election cycles: 2010, 2015, 2020, 2025, 2027, and now back to 2026, fueling skepticism that oil has become a political promise.

With President Museveni seeking re-election in 2026, some view the June 2026 deadline as both symbolic and strategic.

Delays have also created cost uncertainty. Businessman Patrick Bitature, for instance, borrowed USD 10 million, anticipating an oil-led boom in hospitality, only to find himself in prolonged court battles instead.

Other companies such as Bemuga Group, which had invested in transportation equipment, have also had their fingers burnt.

Uganda’s delays are structural. Transporting waxy crude requires a heated pipeline, thousands of welds, and coordination across borders. Each delay adds months and millions of dollars in costs.

Environmental and governance challenges persist. EACOP has faced a fair share of lawsuits, European Union resolution on the project’s environmental impact, and NGO campaigns over displacement and climate impacts.

Government, however, insists the project meets global standards, but compliance takes time and money.

The progress so far

Uganda’s oil drilling has advanced. The Hoima–Buliisa road winds gracefully through the Great Rift Valley, revealing the country’s petroleum heartland.

The three anchor projects, Tilenga (TotalEnergies), Kingfisher (CNOOC), and EACOP (UNOC and partners), are in their final construction stages.

At Tilenga, 149 wells have been drilled out of a planned 450. The Central Processing Facility, with a 190,000-barrel-per-day capacity, is nearing completion. The 96-kilometer Tilenga feeder pipeline is also almost done, with 75 kilometers welded and pressure-tested.

Over 11,700 Ugandans, representing 91% of TotalEnergies’ workforce, now hold roles once dominated by foreigners.

More than 200 have trained abroad in France, Malaysia, and Oman, returning as certified drilling engineers, technicians and safety experts.

More than 280 Ugandan companies now supply goods and services to Tilenga, with local procurement valued at over USD 747 million.

TotalEnergies’ sustainability programme has restored 118 hectares of land, removed 3,000 animal snares, and partnered with the Uganda Wildlife Authority to track wildlife migrations using GPS collars.

The Kingfisher project

Across Lake Albert in Kikuube District, CNOOC’s Kingfisher Project tells a complementary story.

The LR8001 automated rig has drilled 17 of 31 wells. The Central Processing Facility, designed for 40,000 barrels of daily capacity, is nearing completion.

CNOOC’s community programmes have trained over 1,000 Ugandans in welding, heavy machinery operation, and pipefitting, while 350 local contractors have joined the supply chain.

The Buhuka Gravity Water Scheme now supplies clean water to over 13,000 residents.

Two demonstration farms showcase improved rice and millet varieties, turning subsistence farmers into modern agripreneurs.

UNOC has emerged as the sector’s conductor, managing the state’s commercial interests and coordinating production, transport, and trade.

Its flagship project, the East African Crude Oil Pipeline, is over two-thirds complete. More than 1,100 kilometres of line pipe have been delivered, with 800 kilometres welded, 300 coated, and 115 kilometres buried.

Pump stations and the Tanga marine jetty are under construction. Once operational, EACOP will transport 216,000 barrels of oil per day, transforming Uganda into a regional exporter.

UNOC is also spearheading the Kabalega Industrial Park, a 29-square-kilometer hub for the estimated USD 4 billion refinery, petrochemical plants, warehouses, and agro-industries.

The park is projected to contribute $4.9 billion annually to GDP and create 35,000 jobs.

The Uganda Refinery has completed its front-end engineering design and will produce refined fuels, LPG, and petrochemicals, reducing import dependence.

Since November 2023, UNOC has been the sole importer of petroleum products in partnership with Vitol Bahrain.

By mid-2025, it had received over 37 shipments through transit routes via Kenya and Tanzania.

In Mpigi, the 320-million-liter Kampala Storage Terminal is under development, complementing the existing Jinja facility with a 30-million-liter capacity.

Together, they form the backbone of Uganda’s energy security strategy.

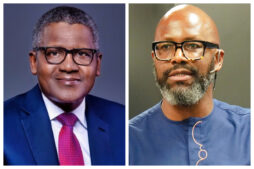

Dangote Appoints MTN Group CEO Ralph Mupita to Fertilizer Board

Dangote Appoints MTN Group CEO Ralph Mupita to Fertilizer Board