Imagine a young software developer in Kampala. He’s just finished building a smart-contract application that could help farmers track produce payments without relying on brokers. He’s hopeful, energized, but frustrated. Because while his app runs on cryptocurrency protocols, Uganda doesn’t recognize any of that as legal tender. His innovation, though technically sound and globally viable, floats in a legal grey zone. That’s not just his dilemma—it’s Uganda’s. Back in October 2019, Finance Minister Matia Kasaija declared before the country that government does not recognize any cryptocurrency as legal tender. It was a firm stance, probably grounded in caution, but one…

Uganda Sits on a Trillion Shilling Crypto Market – But Without Rules, Clarity or Direction

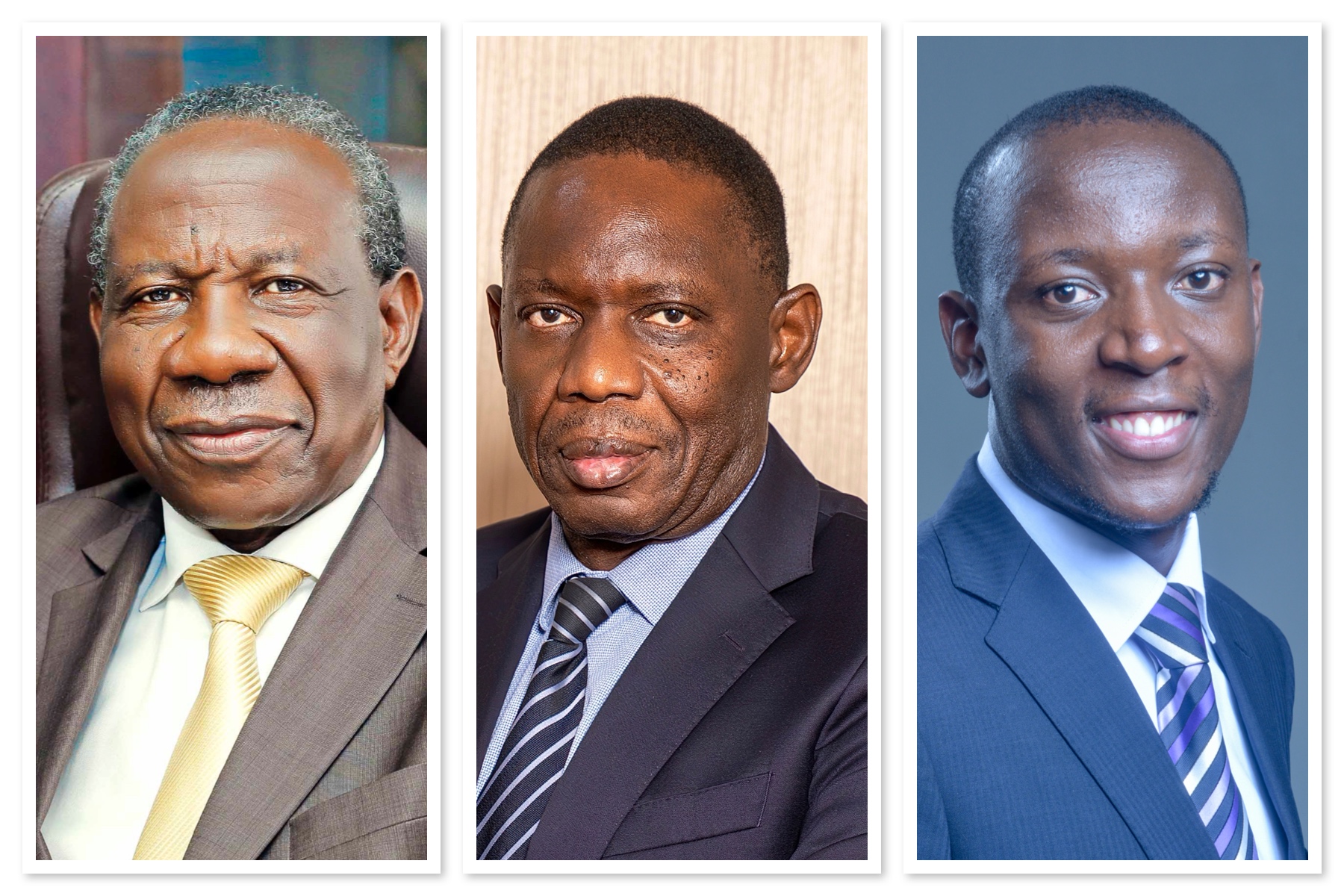

Left-Right: Finance Minister Matia Kasaija, Bank of Uganda Governor Michael Ating-Ego, and Lawyer Silver Kayondo. The Finance Ministry and Bank of Uganda maintain that cryptocurrencies are not legal tender in Uganda. Kayondo’s attempt to find legal means of regularizing cryptocurrency through the court was dismissed.