Markets in downtown Kampala remain lively, yet many traders quietly admit sales are slowing and loan costs are biting harder.

It is the classic squeeze: weak consumer demand meeting tighter credit.

Uganda’s headline growth numbers tell a different story. GDP expanded by 6.1% in the 2023/24 financial year, up from 5.3% the year before, supported by a rebound in manufacturing, construction, and services.

Per capita income also edged up to $1,146 from $1,081. But firm-level conditions are tighter.

Private-sector credit rose 7.3%, well below investment needs, while lending rates hover near 18%, squeezing SMEs.

At the same time, Uganda’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains stuck around 13–14%, despite URA collecting Shs27.8 trillion last year. Fiscal room to support businesses is therefore narrow.

Inflation, once the pressing worry, has cooled. By June 2025, headline inflation stood at 3.2%, down sharply from 8.8% the year before.

A stronger shilling, steady inflows from coffee, remittances, and foreign investment helped ease price pressures.

But that very firmness of the currency, while good for importers, has chipped away at exporters’ margins, making factories and farms more cautious.

The contradiction is that Uganda looks strong from the top line but fragile at the firm level.

Growth is rising, inflation is tamed, and oil projects inch closer, but private credit is weak, fiscal space is tight, and too many young Ugandans remain jobless.

“While we saw a modest drop in business confidence, particularly among micro and small enterprises, the outlook remains positive.

The decline reflects real but manageable challenges in the operating environment,” says Dr Brian Sserunjogi, Senior Research Fellow, Economic Policy Research Centre.

As for Moses Kaggwa, the acting director of Economic Affairs at the Ministry of Finance, government interventions have supported stability, but “fiscal consolidation” and “low tax revenues” continue to constrain policy space.

Growth is up and inflation is tame, but credit is weak, fiscal room is thin, and too many young Ugandans remain jobless.

This is the stage on which Uganda’s 2026 election will play out.

Eight candidates are on the ballot, but three manifestos matter most for business and investors, because they represent the poles of Uganda’s political economy.

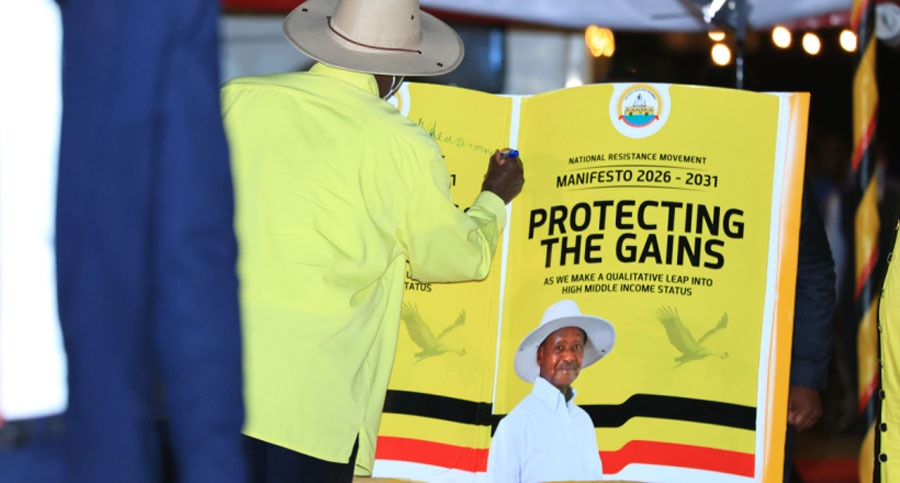

The ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) carries the weight of incumbency and nearly four decades of shaping the policy environment.

President Museveni’s NRM seeks to defend a record of infrastructure and continuity.

Robert Kyagulanyi’s NUP campaigns on accountability and jobs, Nathan Nandala Mafabi’s FDC stresses fiscal discipline and household incomes.

The National Unity Platform (NUP) commands the largest share of youthful opposition energy and has already framed its agenda around accountability and jobs.

And the FDC brings fiscal discipline and a reputation for sharp oversight, seeking to reassert itself as the country’s technocratic opposition.

For each, the manifesto is a blueprint for how they claim they can fix Uganda’s economic contradictions.

NRM Manifesto: Infrastructure and continuity

The NRM manifesto presents itself as the guarantor of stability and continuity, with a private sector message built on infrastructure.

It pledges to “expand, improve and rationalize” roads, railways, pipelines, ICT backbones, and energy, shifting cargo from roads to rail and pipeline so roads serve passengers and light goods.

This is paired with agro-commercialization: “the global demand for coffee is $460 billion… dairy $893 billion… but the country also needs low value products such as cotton, tea, maize, sugar-cane… If you do these on a big scale, you will get good money.”

The model favours scale, nudging smallholders into commercialization while encouraging large landholders to maximize acreage.

For manufacturers and agro-processors, the alignment is clear. As the manifesto says: “the factories are for adding value… then, there is the knowledge economy of automobiles, electronics, vaccines, etc.”

It emphasizes Uganda’s pitch for outsourcing: “A country like India earns $49.87 billion from BPOs. Uganda can do well there.”

But execution remains Uganda’s weak link. Take the Kampala–Entebbe Expressway. The official contract for the 49.56 km project shows a cost of $476 million (about $9.2 million per km), more than four times the typical cost of a similar four-lane highway, according to the initial infrastructure records in the Ministry of Works that differ from what was spent after the project concluded.

In the roads sector more broadly, the Office of the Auditor General has recently noted that variation-of-price payments (for materials/labour) ranged from 10.5% to more than 60% of contract value, and paid-out overpayments of UGX 6.7 billion were flagged for investigation.

Meanwhile, the Standard Gauge Railway project is stuck: a January 28, 2025, parliamentary update reported a UGX 686 billion ($186 million) shortfall, delaying the scheme.

Even the party manifesto behind the initiative acknowledges the weakness: “the under-budgeting that had crept back and the suspected inflation of costs, will be firmly dealt with.”

Taken together, cost escalation, delays, and weak oversight make the infrastructure promise an execution risk.

For business, NRM offers predictability: “the same macroeconomic policy mix, the same state-led infrastructure push.” But this favours firms with networks and buffers.

According to the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority (PPDA) Fourth Procurement Integrity Survey (July 2020), “big firms have an advantage” in public contracts.

Meanwhile, in a July 30, 2025, parliamentary briefing, Works Minister Edward Katumba Wamala disclosed that 27 major road and bridge projects were “suspended or significantly slowed down” because of delayed payments and a UGX 2.47 trillion funding gap.

NUP Manifesto: Governance reset as business policy

NUP reframes governance reform as economic reform, seeking to seal leakages, secure land, mobilize diaspora capital, and turn waste into wages.

It starts by saying that: “successive governments have failed to unite our people, respect our freedoms, and guarantee equal opportunities.”

To NUP, waste and graft are not side shows; they are the heart of why businesses struggle, services falter, and public trust erodes.

The Inspectorate of Government estimates that Uganda bleeds UGX 10 trillion every year to corruption.

But between January 2022 and June 2023, it managed to claw back only UGX 7.99 billion, a rounding error compared to the loss.

The Auditor General’s 2022/23 Report told a similar story: pension and gratuity over-payments of UGX31.2 billion, and procurement loopholes worth more than UGX10 trillion.

In September 2025, Parliament’s Public Accounts Committee cut even closer to the bone, warning that “borrowed money is wasted on enriching a few individuals, government is losing money through inflated contracts and weak supervision.”

It is from this landscape that NUP argues that cleaning up government is, in fact, an economic policy.

It argues that if a fraction of that lost UGX 10 trillion were saved, it could finance jobs, SMEs, or schools without new borrowing.

This is why its manifesto makes the bold promise to “create 10 million jobs by 2032”, with the lion’s share (60%) from manufacturing, another quarter from tourism, and the rest from sports and the creative economy.

The strategy is to diversify growth engines beyond subsistence farming, while linking agriculture to human capital through a nationwide school feeding programme.

By guaranteeing steady demand for farmers’ produce, it hopes to boost rural incomes while improving nutrition and learning outcomes.

Land, too, is central. For NUP, “stopping land grabbing and guaranteeing secure land rights for all” is about unleashing private investment where farmers and entrepreneurs are more willing to take risks when they know their property is safe.

And the diaspora, often overlooked, is repositioned from sentimental remittances to strategic capital.

In the 2024/25 financial year, Ugandans abroad sent home $1.57 billion, but in NUP’s words, this is “largely underutilized.”

NUP plans to tap that flow as a catalyst for enterprise and global competitiveness.

In short, NUP is telling businesses and households alike that the money to transform Uganda already exists; it is simply being siphoned away.

By sealing leaks, securing land, and channeling diaspora capital, it argues that it can turn waste into wages and lost opportunity into jobs.

For businesses, the appeal is a level playing field.

FDC Manifesto: Bottom-up economics and household liquidity

The FDC manifesto is framed under the theme “Fixing the Economy; Money in our Pockets,” placing immediate household incomes and inclusivity above big infrastructure promises or governance resets.

Where NRM points to roads and dams, and NUP to constitutional reform, FDC bluntly declares that “Ugandans are living under extreme duress because of the harsh economic conditions”.

“We have a young, energetic but unemployed youth, citizens that are burdened with expensive health care bills and dysfunctional health facilities, businesses are closing because of high taxes, and the country is on the verge of bankruptcy due to reckless management of our financial resources.”

At the heart of its economic plan is agriculture. The manifesto highlights subsectors as anchors: “Coffee: the black gold for job creation; fisheries: the blue economy; livestock: production for job creation; cotton: The white gold; tea: the money magnet.”

This diagnosis mirrors official data. According to the Ministry of Finance, Directorate of Economic Affairs Annual Report 2023/24, agriculture still employs 65–70% of Ugandans but contributes less than 24% of GDP, a sign of low productivity and weak value addition.

The collapse of cooperatives in the 1990s left farmers vulnerable to middlemen, who skim off most of the value in coffee, cotton, and dairy.

The Auditor General, in a 2022 report, warned of “loss of farmer incomes due to lack of collective bargaining and weak cooperative systems.”

This explains why cooperatives occupy a central place in FDC’s vision. As the manifesto puts it: “We promise to put money in your pockets by reviving the cooperative unions.”

Evidence suggests this is more than nostalgia. Farmers in the Bugisu Cooperative Union, for instance, consistently fetch higher coffee prices than those selling individually, because they pool output and access export markets directly.

Development economist Augustus Nuwagaba, who is also the Deputy Governor, Bank of Uganda, has long argued that without strong cooperatives, farmers remain “atomized and vulnerable to middlemen.”

Fiscal discipline is another pillar. FDC vows to “control Uganda’s debt burden,” arguing that reckless borrowing is crowding out private sector credit.

By 2024, public debt stood at $29.1b, about 52% of GDP, up 18% in a year.

Debt servicing consumes above 30% of domestic revenues, leaving little for development.

Bank of Uganda officials have admitted that heavy domestic borrowing by government has pushed up interest rates, squeezing SMEs out of affordable loans.

Infrastructure is not dismissed but redefined. Roads, power, ICT, and housing are included in FDC’s plan, but only as enablers.

The manifesto insists that infrastructure has little impact unless households have money to use it.

This aligns with the World Bank’s 2023 assessment that Uganda’s network has grown but remains “underutilized because household incomes are too low to afford consistent access.”

For business, the signals are that agribusiness, cooperatives, and rural SMEs will be prioritized. Input suppliers, processors, and exporters linked to farming stand to gain from a more liquid rural economy.

But FDC’s agriculture-heavy model carries vulnerabilities. The Uganda National Meteorological Authority reported in 2022 and 2023 that erratic rains wiped out harvests in maize and coffee-growing districts, underlining how climate shocks can unravel rural incomes.

In comparison, FDC is less ambitious on digital transformation than NRM or NUP. But it is stronger on inclusivity and household-level impact, betting that lifting rural incomes first will create the demand base that infrastructure and industry need to thrive.

The manifesto test

Uganda’s three main manifestos must be tested against the real conditions that businesses face today: limited credit, a tight fiscal space, stubborn youth unemployment, fragile export competitiveness, and climate vulnerability.

These challenges were highlighted in the Ministry of Finance’s 2023/2024 Directorate of Economic Affairs Annual Report, released on October 4, 2026.

The first challenge is credit and the cost of finance. Bank of Uganda reports that private sector credit growth remains subdued, with lending rates hovering around 17–18% in 2024, levels that discourage SMEs and keep investment sluggish.

For the NRM, the assumption is that infrastructure and industrial parks will draw investment, but as Henry Sebukeera, Advisor on Budget at the Ministry of Finance, says in an interview, “what a business personally needs… is a competitive environment”.

“These involve issues like electricity, transport, and access to low-cost finance or capital. And it does not matter how much tax you cut if businesses are still getting capital expensively.”

NUP, by focusing on curbing corruption and enforcing public finance accountability rules, promises to reduce the hidden costs that inflate credit risk.

The logic is that the Inspectorate of Government estimates Uganda loses UGX 10 trillion annually to corruption, but recoveries remain negligible.

Cutting these leakages would expand fiscal space and reduce the uncertainty that banks build into lending rates, lowering costs for SMEs.

FDC, on the other hand, seeks to inject liquidity at the grassroots level by reviving cooperatives.

Its plan hinges on restoring collective bargaining power and finance access through SACCOs and a revived Cooperative Bank.

At the National Cooperative Conference in Kampala in September 2025, the Uganda Cooperative Alliance outlined steps toward re-establishing a Cooperative Credit & Savings Society as a precursor to a full cooperative bank, designed to channel affordable credit directly to farmers and rural enterprises.

Research by the National Planning Authority in 2023 similarly concluded that empowering cooperatives with finance, value-chain integration, and bargaining power is essential to raise productivity and incomes.

Together, these approaches show how both parties aim to tackle the financing constraint: NUP by reducing governance risks, FDC by mobilizing bottom-up liquidity.

The second test is fiscal space. Uganda’s debt has risen to 52% of GDP, and debt servicing already consumes more than a quarter of revenues, according to the Ministry of Finance’s State of the Economy Report of August 2025.

The International Monetary Fund’s 2024 Article IV Consultation Staff Report, released on September 11, 2024, cautioned that “while public debt is sustainable, low tax revenues constrain Uganda’s fiscal policy space.”

Uganda’s tax-to-GDP ratio of 13–14% remains well below the Sub-Saharan African average of 17–18%, underscoring the challenge.

Here, the manifestos diverge. NRM offers continuity but is weakened by a record of arrears and cost overruns that crowd out development spending.

NUP argues that recovering even part of the UGX 10 trillion lost annually to corruption, as estimated by the Inspectorate of Government, would create fiscal room for investment.

Uganda, Sebukeera adds, already forgoes UGX2–3 trillion annually in tax holidays and exemptions, making the real challenge not headline tax cuts but how efficiently revenue is raised and spent.

FDC takes the most austere line: “control Uganda’s debt burden” is its headline promise, aligning with what oversight institutions and investors have long demanded.

Jobs are another decisive fault line. Only about one in four Ugandans is in wage employment, with most youth cycling through low-productivity work, according to data from Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

NRM’s bet is that factories, industrial parks, and oil projects will gradually absorb labour if costs fall as promised.

NUP’s bet is that SMEs and startups, freed from corruption and predatory procurement practices, can hire more quickly.

This reflects Sebukeera’s point that competitiveness, not populist tax cuts, is what enables firms to grow and employ.

FDC’s strategy is to turn subsistence into cash incomes by rebuilding agricultural cooperatives and rural value chains.

This can deliver immediate impact in the countryside but is vulnerable to climate shocks; the Uganda National Meteorological Authority warned in 2022 and 2023 that erratic rainfall destroyed harvests in major maize and coffee districts, wiping out rural incomes overnight.

Exports and competitiveness present another divide. A stronger shilling has lowered import costs but squeezed exporters’ margins.

Manufacturers and farmers alike face declining returns unless productivity rises.

NRM believes scale and infrastructure will restore competitiveness. NUP insists that cutting rent-seeking, delays in refunds, and permit bottlenecks is equally critical.

FDC places faith in collective bargaining through cooperatives to improve farm-gate prices and help farmers meet export standards.

Sebukeera’s emphasis on government’s “ATMS” priorities, agro-industrialization, tourism, minerals, and science and technology, reinforces this point that “whichever party wins, businesses that align with these priority sectors are the most likely to benefit from state support.”

In the end, each manifesto offers businesses a different path.

For large contractors and foreign investors, NRM’s continuity and scale may feel safest. For SMEs and startups, NUP’s promise of a level playing field is potentially the most transformative.

For agribusiness and rural financiers, FDC’s cooperative-driven model could expand markets and liquidity.

But as Sebukeera reminds, the deeper issue is competitiveness: “If businesses are still getting capital expensively, they are not able to get power at below five cents, and their logistics are still expensive … it does not matter how much tax you cut.”

This is the measure of survival: NRM’s infrastructure push, NUP’s governance reset, and FDC’s cooperative revival each offer partial answers, but none fully overcome the realities of credit, fiscal space, and competitiveness.

In practice, only the promises that tangibly lower business costs and raise productivity will survive contact with Uganda’s business reality.

Ruparelia Foundation to Hold Free Eye Camp in Bukedea in Honour of Rajiv Ruparelia

Ruparelia Foundation to Hold Free Eye Camp in Bukedea in Honour of Rajiv Ruparelia