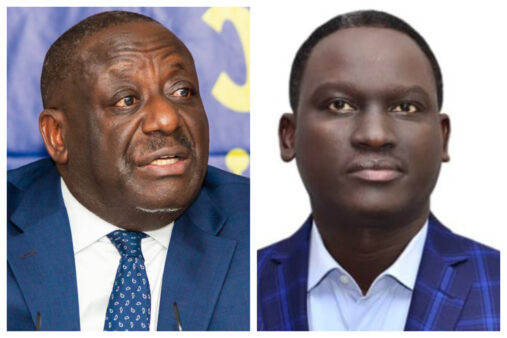

He speaks candidly about the evolution of Uganda’s legal profession—its need for mentorship, specialisation, and ethical renewal—while making a compelling case for policy-driven innovation, carbon trading, and collaboration across Africa’s legal and trade systems. As a thought leader and mentor, Kenneth embodies a new model of transformational leadership in the legal profession, one grounded in service, adaptability, and the courage to challenge convention. Beyond the legal profession, Kenneth reveals a deeply personal side: his faith-driven philosophy, love for hiking and mindfulness, and a firm belief that true success lies in impact, not income. This is the story of a lawyer…

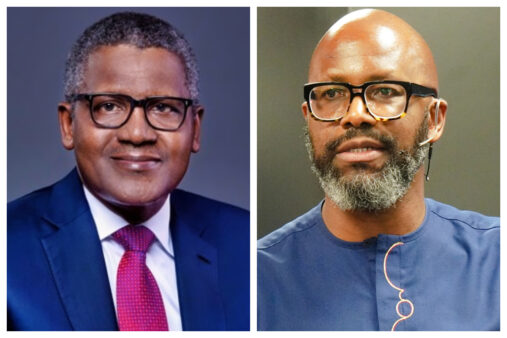

Kenneth Muhangi: Building a New Generation of Lawyers Through Pragmatism, Mentorship, and Innovation In this deep conversation with CEO East Africa Magazine, Kenneth Muhangi, Partner at KTA Advocates, takes us on a journey from his humble beginnings in Masaka to becoming one of Uganda’s leading voices in intellectual property, technology, and sustainability law. A pioneer in fields spanning digital trade, fintech, data protection, and climate policy, Kenneth reflects on how early family values of discipline, learning, and love shaped his worldview and work ethic.

Kenneth Muhangi — a lawyer, teacher, reformer, and thought leader — embodies a new generation of legal leadership defined by service, mentorship, integrity, and impact. With a career spanning technology law, intellectual property, sustainability, and policy, he continues to champion practical, ethical, and purpose-driven change across Uganda’s legal and governance landscape.