Stanbic Bank Uganda and its parent holding company, Stanbic Uganda Holdings Limited (SUHL), are battling a sweeping transfer-pricing assessment by the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA), now before the Tax Appeals Tribunal under TAT Application No. 170 of 2025 — the latest in a growing wave of transfer-pricing disputes, as URA intensifies audits on multinationals — a campaign that has swept through most large foreign-owned firms in recent years.

At the core of the Stanbic-URA tax dispute lies a critical question: Did Stanbic Bank’s and SUHL’s related-party charges reflect true market value — or did the bank understate taxes through mispriced internal transactions?

The outcome carries implications far beyond one bank — touching the broader corporate tax environment.

A dispute nearly a decade in the making

The transfer-pricing dispute dates back to August 2017, when the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA) opened a review into Stanbic’s related-party transactions for the period 2012–2016 — five financial years that together represented billions of shillings in cross-border service charges, royalties and system costs.

In 2021, URA widened the review to capture 2017–2019, effectively bringing eight consecutive years of intra-group dealings under scrutiny.

In the years following URA’s 2021 decision to extend the review to 2017–2019, the case advanced gradually through exchanges and documentation. Momentum picked up again in May 2024, when URA issued further information requests, signalling that the review was entering its final phase.

The pace then accelerated. In February 2025, URA issued a formal transfer-pricing tax assessment to Stanbic. Barely a month later, in March 2025, the authority followed up with a detailed audit report, setting out the assumptions, calculations and reasoning behind the assessment.

URA’s initial position placed Stanbic’s principal exposure at UGX 122.6 billion. As computations were refined and additional adjustments were layered in, the figure rose to UGX 133.7 billion — excluding interest and penalties (which, if applied, could lift the final obligation significantly higher).

Amid objections and recalculations, a working dispute figure of roughly UGX 117.8 billion emerged — the amount broadly associated with the core contested items.

Stanbic filed a formal objection, arguing the charges were priced at arm’s length under OECD-aligned policies. That objection escalated the matter to the Tax Appeals Tribunal (TAT Application No. 170 of 2025) — transforming a technical audit into a high-stakes legal battle.

URA’s findings focus on pricing, allocation and documentation, rather than whether services existed at all.

In other words, the tax authority accepts that Stanbic interacted with its Group — it simply questions how much was paid, who should have borne the cost, and whether the evidence was prepared in real time.

Franchise and Management Fees — URA questions value for money

This is one of the major issues in URA’s audit. The tax authority argues that while SBSA — Stanbic’s parent — undoubtedly provides oversight, brand guidance and group support under the franchise arrangement, the amounts charged to the Ugandan subsidiary appear out of proportion to the value actually realised locally.

In URA’s view, a significant share of the franchise and management fees covered activities such as group policy alignment, governance oversight, brand supervision and participation in group-wide frameworks. These, it says, look more like routine coordination than bespoke advisory work that would materially transform Stanbic Uganda’s commercial performance. On that basis, the authority classifies many of the charges as “low-value-adding services,” which should attract only modest, cost-plus mark-ups, not premium franchise-style pricing.

URA also suggests that some of the head-office functions billed to Uganda served primarily to protect the Group’s own risk and reputation, placing them closer to shareholder functions — activities a parent typically absorbs itself, rather than passing through to subsidiaries.

On top of that, URA raises the issue of duplication. It argues that certain support activities — for example, elements of risk coordination, technology governance or operational oversight — appeared to be already covered under separate intra-group service arrangements, yet still surfaced again within the franchise fee. In URA’s interpretation, this amounted to Uganda paying twice for parts of the same support.

Taken together, these concerns lead URA to conclude that portions of the franchise and management charges failed the arm’s-length test — meaning an independent, unrelated bank would not reasonably have accepted the same pricing structure — and therefore the authority re-priced the transactions downward in its assessment.

Group technology platforms (Calypso, Business Online and others) — who was really footing the bill?

With technology charges, URA’s concern is not about the existence or importance of the systems themselves — Calypso, Business Online (BOL), and other platforms are clearly central to how Stanbic operates. The dispute lies instead in how those costs were distributed within the Group.

URA argues that Stanbic Uganda was at times billed for technology upgrades, system enhancements and post-implementation support that appeared to serve multiple subsidiaries across the network. In several instances, the authority believes, the economics looked less like Uganda paying for its own usage, and more like Uganda absorbing a share of Group-wide investment — including projects that improved functionality for affiliates far beyond Kampala.

The concern is straightforward: under arm’s-length principles, a subsidiary should bear only the portion of the cost that reflects its own benefit. URA contends that, in practice, some invoices seemed to roll together development, regional roll-outs and ongoing global maintenance, with Uganda picking up more than what could be clearly traced to its operations.

In addition, URA questions whether certain post-sale or “change-the-bank” enhancements were charged twice in different forms — first as part of broader platform development costs, and later as continuing service fees — effectively blurring the line between capital investment and routine support.

Put simply, the tax authority worries that Stanbic Uganda may have unknowingly subsidised broader Group technology ambitions, and that the allocation models used did not always reflect what two independent parties — negotiating at arm’s length — would reasonably have agreed.

Trade Processing Services (TPS) — URA’s key duplication allegation

Of all the items under review, Trade Processing Services (TPS) is one of the areas where URA is most forceful. The authority believes that Stanbic Uganda was effectively charged twice for the same back-office work.

According to URA, many of the tasks covered under TPS — validating trade instructions, handling confirmations, processing settlements, and reconciling positions — already appeared within other group service modules that Stanbic was paying for. In other words, the operational machinery that moves trades from the front office to completion was already being funded elsewhere in the inter-company agreements.

Yet, URA argues, those same functions then reappeared as a separate TPS line item, now billed again under a distinct label.

To illustrate its concern, URA describes situations in which the same activity seemed to surface under different labels. In some cases, the bank’s risk and operations support unit was already charging a fee for overseeing the flow of transactions. The regional processing centre, meanwhile, billed separately for executing much of the back-office work tied to those trades. Yet, URA argues, a third charge then appeared under Trade Processing Services — effectively described as “trade processing” — even though, in the authority’s view, the substance of the work overlapped significantly with functions that had already been paid for.

From URA’s perspective, nothing materially new was being provided under TPS — no additional team, no incremental functionality, no value-enhancing layer. What changed was simply how the cost was described.

If this interpretation is correct, URA says, it constitutes double recovery: a situation where a multinational shifts profit by billing the same activity more than once. Transfer-pricing frameworks treat this as one of the clearest violations, because profits move, but no new economic value is created.

In plain terms, the tax authority fears that TPS has become a second billing channel for work already captured elsewhere— inflating intra-group charges and eroding the Ugandan entity’s taxable income.

Global markets adjustments — URA says reported income looked unusually thin

In the global markets portfolio — covering treasury, trading and structured deals — URA did more than question costs. It turned its attention to how profits were shared between Stanbic Uganda and its affiliated entities.

URA’s position is that, once inter-company charges were removed — fees for funding support, pricing tools, trading coordination or risk hedging provided by the Group — the earnings left on the Ugandan books sometimes appeared “unusually thin.” In the authority’s eyes, the pattern suggested that a meaningful portion of value created in Uganda migrated to the parent or regional hubs through transfer-pricing mechanisms.

To explain its concerns, URA points to situations where, in its view, the economics of certain transactions tilted away from Uganda. In some cases, group entities provided pricing models or structuring expertise and then retained a substantial portion of the resulting margin. In others, cross-border trades were routed through affiliated dealing desks, with profit allocations favouring offshore entities even though the originating client relationship — and much of the associated risk — remained in Uganda. URA also notes examples in which inter-company charges for funding and hedging appeared to consume most of the deal economics before they ever reached Stanbic Uganda’s bottom line.

URA did not argue that such collaboration should never occur — modern banking often relies on centralised expertise. Rather, it questioned whether the share of profit retained offshore reflected the true contribution of each party.

So the tax authority effectively re-priced parts of these transactions. Its objective, as it frames it, was to reconstruct what Stanbic Uganda would likely have earned had it executed those trades with independent third parties, paying only for services that could be clearly justified at arm’s length.

In short, URA believes that some profit allocations in global markets did not mirror economic reality — and that correcting them was necessary to restore what it views as Uganda’s fair share of taxable income.

Timing and evidentiary rigour — URA says the paperwork came too late

Beyond disagreements over pricing, URA places significant weight on when Stanbic prepared and submitted its supporting documents.

URA’s position is that some of the key analyses and explanations the bank relied on — including transfer-pricing reports, functional analyses and clarifications around specific cost allocations — were not available at the time the transactions occurred. Because they were presented only later, during the audit and objection processes, URA treats them as “new information,” not contemporaneous documentation.

The Tribunal application shows how this played out in practice.

In one instance, the Applicants highlight that they submitted evidence to URA on 14 February 2025, yet the assessment had already been issued on 17 February 2025 — raising the question of whether URA meaningfully reviewed those materials before finalising its position. The Applicants argue that this pattern repeated across several items, where explanations were provided, but URA proceeded on the basis that documentation was insufficient or out of time.

URA, however, maintains the opposite: that documentation created or updated years later cannot cure earlier non-compliance. From its perspective, transfer-pricing rules require taxpayers to have the rationale for the pricing, the evidence showing benefits, and comparable benchmarks already in place when the transactions occur, not assembled after an audit notice has been issued.

This is why URA insists that it was entitled to reconstruct pricing and disallow charges where, in its judgment, the original documentation was incomplete, unclear, or not contemporaneous.

In essence, timing becomes a substantive issue: URA is not only disputing what Stanbic paid and charged within the Group, but how well — and how early — the bank documented its reasoning, and whether the later submissions were truly evidence of prior policy, or simply responses created during the dispute.

Stanbic’s defence: URA misapplied the rules, ignored evidence, and went out of time

In its appeal, Stanbic builds a broad defence that blends legal arguments with detailed technical rebuttals. First, the bank challenges the very foundation of the assessment, arguing that a significant portion of the years under review was issued outside the legal assessment window and is therefore time-barred. Beyond procedure, Stanbic contends that URA misapplied the arm’s-length principle, disallowing legitimate cross-border charges even where the tax authority did not dispute that services were actually rendered. In Stanbic’s view, URA effectively re-priced some transactions to zero, a position the bank says contradicts both OECD guidance and how independent parties behave in real markets.

Issue by issue, Stanbic pushes back. On the franchise and management fees, it argues that these arrangements are internationally recognised, provide tangible strategic value and brand benefits, and were priced using accepted benchmarking methods. On software and platform costs — including Finacle, Calypso and Business Online — the bank says URA ignored binding inter-company agreements and misunderstood the nature of cost-sharing and licensing, which in Stanbic’s view legitimately allocate technology development and maintenance costs across the Group. It rejects claims of duplication around Trade Processing Services, insisting the charges relate to distinct functions rather than the same service being billed twice.

In the Global Markets business, Stanbic argues that URA oversimplified a complex, collaborative trading model that spans pricing desks, risk hubs and client coverage across multiple jurisdictions — and that the resulting adjustments fail to reflect how value is actually created and shared within modern banking groups. The bank also disputes URA’s treatment of IT “change-the-bank” projects, insisting these were real costs incurred at arm’s length, and challenges the view that withholding tax should apply to disallowed amounts.

Finally, Stanbic rejects the accusation that it lacked adequate support. The bank maintains that documentation existed, was supplemented during engagements, and that URA either failed to meaningfully consider what was provided or unfairly dismissed updates as “new information.” In several instances, Stanbic says the authority formed conclusions without fully weighing the contractual evidence and explanations on record.

Taken together, the bank’s position is clear: the dispute is not about evasion, but about interpretation — and Stanbic insists that when the law, contracts and economic substance are correctly applied, the contested charges fall within arm’s-length norms and the assessment cannot stand.

Stanbic: confident, cooperative — and insisting the process is routine

Stanbic firmly rejects the suggestion that URA’s assessment points to non-compliance.

Instead, the bank presents itself as fully cooperative, transparent — and engaged in what it describes as a normal part of doing business as a large multinational bank.

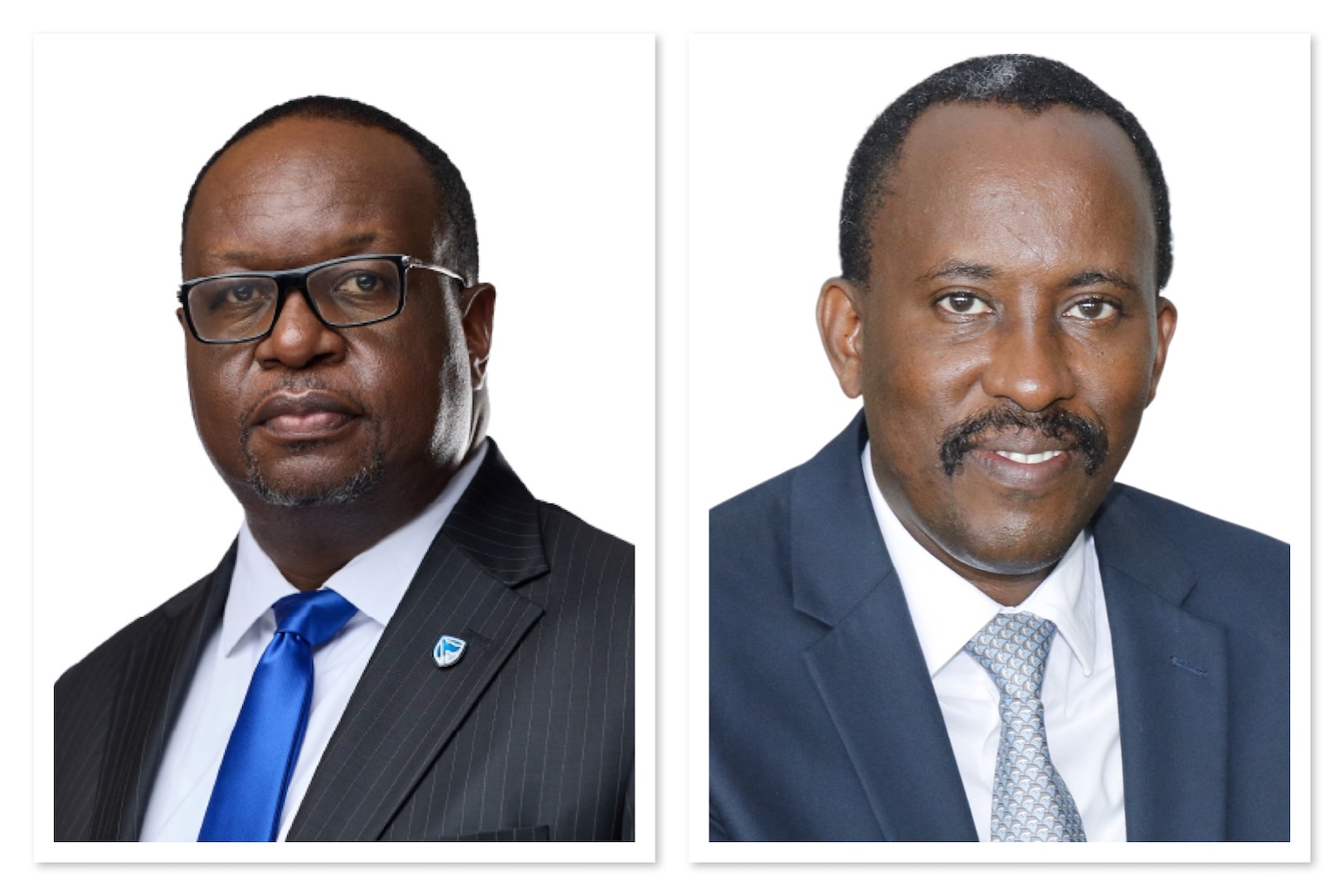

Speaking to the media about the matter during the release of the H1 2025 results in August 2025, Chief Financial Officer Ronald Makata stressed that the institution remains comfortable with its tax posture: “…we are very tax compliant… This is a normal process that organisations go through. We actually invited URA to review our environment — and we are now following the legal process.”

Group Chief Executive Mumba Kalifungwa reinforced that message, anchoring it in Stanbic’s broader tax contribution: “…we contributed over UGX 400 billion in taxes last year and UGX 273 billion year-to-date. Our policy is zero tolerance for non-compliance, and we enjoy a constructive relationship with URA.”

Overall, Stanbic maintains that the tax dispute is technical and procedural, rooted in the interpretation of transfer-pricing rules — not evidence of misconduct.

If Stanbic loses — the risks extend beyond the tax bill.

If the Tribunal were to side with URA, the implications for Stanbic would go well beyond the size of the final tax assessment. Analysts note that an adverse ruling could ripple through several parts of the business simultaneously. A confirmed liability — particularly once penalties and interest are added — would inevitably place pressure on earnings, potentially reducing the pool available for dividends, tightening capital planning decisions, and weighing on market sentiment toward Stanbic Uganda Holdings Limited (SUHL).

There is also a reputational dimension. Stanbic is not only one of Uganda’s largest taxpayers; it is also a key partner in tax collection. A judgment suggesting that parts of its intra-group pricing were inappropriate could bruise perceptions, prompt closer scrutiny of future transactions, and introduce a more cautious tone in dealings with regulators — even if the dispute itself remains fundamentally technical rather than ethical.

Perhaps most sensitive is what a ruling in URA’s favour might imply about group-level charges. If the Tribunal were to uphold arguments around duplication, double payments or misallocated costs, it could encourage questions from minority shareholders about whether certain intra-group arrangements may, at times, have tilted against the Ugandan entity’s minority shareholder interests. That would not automatically imply wrongdoing — and there is, at present, no finding of fraud. Stanbic vigorously denies any suggestion of misconduct and insists the charges reflect legitimate cost-sharing models.

Still, experience elsewhere shows that transfer-pricing rulings confirming duplication often trigger governance reviews, particularly where costs flow from parent companies to listed subsidiaries. Should that happen here, the debate would move from a purely tax question to a broader conversation about transparency, fairness and oversight in cross-border corporate structures.

What happens next

From here, the case will move through Uganda’s tax dispute machinery step by step. The objection has already been filed with URA, and the matter now sits before the Tax Appeals Tribunal as TAT Application No. 170 of 2025, where both sides will argue the technical and procedural merits. Whatever the Tribunal decides may not be the end of the road: the losing party can still escalate the dispute to the High Court and, potentially, further appellate levels.

Why this case will resonate beyond Stanbic

Whatever the final ruling, the case will likely echo across boardrooms far beyond Stanbic. It reinforces three messages that multinationals ignore at their peril: transfer-pricing documentation must be contemporaneous, not reconstructed later; cross-border arrangements involving shared IT and support functions will draw far deeper scrutiny; and any hint of duplicated or double-recovered charges will be aggressively tested.

For many multinational subsidiaries operating in Uganda, the case feels uncomfortably close to home. Investors are watching. Regulators are watching. And tax authorities across the region are sharpening their tools.

Because in the modern tax environment, the biggest controversy isn’t always about the money that moves across borders — it’s about the price attached to it.

How Governments Shut Down the Internet — and the Price Economies Pay

How Governments Shut Down the Internet — and the Price Economies Pay