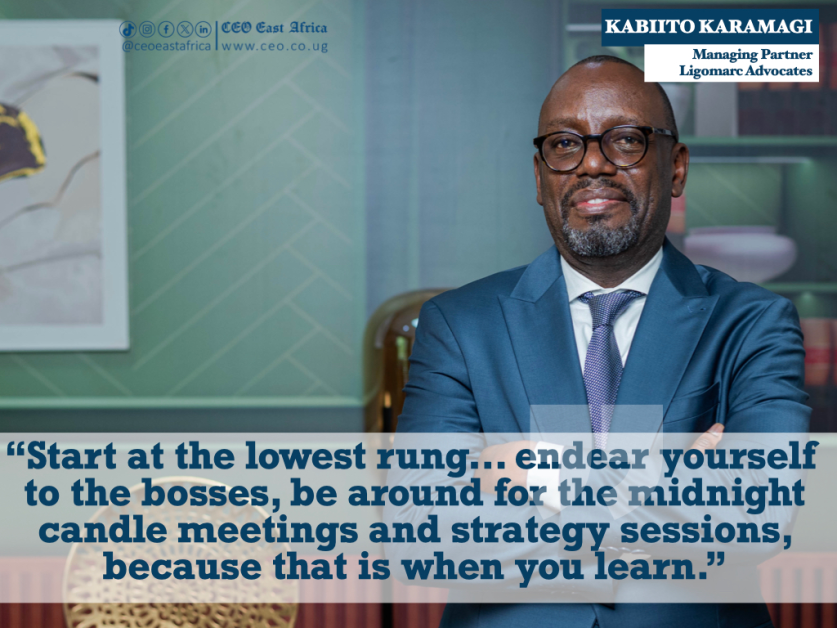

What sets him apart is not just pedigree—but impact. Over a career spanning two decades, Kabiito has led and advised on high-stakes commercial disputes and restructurings worth well over USD 15 billion, including the $13 billion Standard Gauge Railway conflicts, the $2.2 billion Karuma Hydro Power Project litigations, and major financial-sector restructures that have shaped Uganda’s modern economic architecture.

In this deeply revealing sit-down with CEO East Africa Magazine’s Dennis Asiimwe, Karamagi opens with an unexpected but piercing line from Game of Thrones—his way of explaining that justice ultimately sits where society believes it does. It sets the tone for a wide-ranging conversation about the fragility and strength of institutions, the moral tensions of insolvency work, and the misunderstood role of lawyers in national development.

He reflects on his early days at Kalenge Bwanika Kimuli Advocates, the unlikely path that took him from a childhood in political exile to co-founding Ligomarc, and the intellectual scaffolding that built one of Uganda’s most respected legal brands. Along the way, he demystifies some of his most consequential assignments—from steering the Uganda Development Bank restructuring (and the groundbreaking Ojangole cases) to governance reforms at ERA—and the lessons these cases offer about leadership under pressure.

Yet this interview is not all about billion-dollar battles. It is also about the man behind the expertise: the mentor who has supported more than 40 students through Ligomarc’s scholarship program; the reformist who sees the real threat to the profession as not AI, but unprepared young lawyers; the father and leader who believes that discipline and integrity are more valuable than brilliance.

Blending humour, precision, and philosophical depth, Kabiito Karamagi emerges not just as a leading lawyer, but as a thoughtful custodian of Uganda’s evolving legal system. His reflections resonate far beyond law—inviting CEOs, policymakers, and young professionals into a masterclass on resilience, purpose, and the architecture of justice in a changing world.

Glad to finally catch up with you today, Kabiito…

I am glad to be here…

You are the Managing Partner of Ligomarc Advocates. As a way of jumping into this, is there a quotation you can share with us that captures or paraphrases your worldview?

Justice sits where people believe it to be…

That sounds familiar…

I am borrowing from a character in Game of Thrones. It was Lord Varys who said, “Power resides where men believe it resides”, and I think for our judiciary system to be effective, it needs to demonstrate that it can take effect: that people’s grievances can be heard quickly and fairly. Otherwise, people start looking for alternatives…

I never thought I would come across Lord Varys being quoted.

This dynamic impacts the judiciary, which is a self-aware institution that seeks to demonstrate efficacy, because this, in turn, strengthens its relevance. I have been around long enough to have known judges who couldn’t use computers, and to see the system develop into one with a fair representation of IT-competent judges, some of whom are quite academically accomplished. We have far more judges and magistrates with Master’s and other forms of postgraduate degrees and qualifications than before. A recently promoted Judge even held a PhD for years as a Magistrate. We have highly accomplished and well-exposed lawyers leaving juicy positions in top-tier organisations such as PWC to join the bench. I therefore don’t agree with the sweeping accusation that the judiciary is filled with incompetents. That is an insult to the many accomplished lawyers who offered to serve on the bench.

The challenge with the judiciary is one of resources. Yes, the number of judges has been increased, their payments made attractive, but that’s a drop in the bucket given the decades of neglect that the judiciary suffered in the past. More has to be done to deal with the problem of the backlog that neglect caused. There is also a generally perceived problem that the judiciary has gradually lost its independence from the state. Quite true, it appears that some judges have been made to pay for their independence. Maybe this is where the public should step up to protect the judiciary by voting out the overbearing party in charge of the executive at the next polls. The truth is that we know that those disgruntled by things as they are don’t vote. Now, when such critics can’t do as little as go to the polls and vote, perhaps then they should look a hard look at their mirrors before they next speak.

Let’s dial it back a little…back to the beginning. Where it all began, the mundane stuff, like where you were born and raised…

(Laughing) I am your typical 1970s story. When I was born, my dad, who was a Professor of Political Science, was making his final preparations to defend his PhD. For him, this was an intellectual battle, the last in his academic crusade for the ultimate title, and I think that ‘war’ was his mindset, so he named me Karamagi – it means warrior or crusader. My mother, who is from the royal clan of Toro, named me Kabiito as a reflection of her heritage. Those two names shaped me.

We have certainly come across your warrior side.

(Laughing) I hope you have seen my regal side too…

We have been granted a glimpse or two in that regard. What sort of environment did you grow up in?

I grew up in turbulent times. We lived in exile…

A large percentage of people I know from that era went into exile. Why did you guys go into exile?

My father was a lecturer of Political Science, which wasn’t the safest of professions in the 1970s. Add that he had also been a student leader, a Guild President actually, during his time as a student at Makerere University. This sort of got him marked, of course, in those restrictive times.So, we went through the whole array of pandemonium that happened when what you did did not please the authorities. Often on the run, we were sometimes put up by friends and family – something I have always been grateful for – hid in the village, etc…My father initially ran off to the United States and taught in Atlanta, Georgia, but we eventually settled in Nairobi, where He ended up teaching at the University of Nairobi. That move close to home allowed family in Uganda to come visit. So my grandmother and many aunties from the village visited us regularly. We lived in Spring Valley, which was an exclusive part of Nairobi, and still is to date. Eventually, of course, we came back to Uganda, a very beaten-down Uganda at that, in the ‘80s. I had been used to a life where I got a chocolate snack when I was hungry, and here was a whole country where you couldn’t find sugar for tea… (Roars with laughter)

That sounds extreme. Almost like culture shock or something…

I kept wailing that I wanted to go home until my parents hit me with the statement: “This is home.”

And you have stayed here ever since…

(Mocks sadness) It was brutal. When we settled in, my brother Bernard was born…he is a grown man now, working with Bugiri Sugar as their Head of Administration. I also have an older sister, Edith. She works at the African Development Bank in Pretoria, South Africa.

One thing that springs out about that period is that we rarely had households where both parents were employed.

My parents were teachers. My mom trained as a teacher, a schoolteacher. She got interested in radio and television and was encouraged by friends and colleagues to give it a try, which she did. She viewed her audience as a bigger classroom than what she was used to, but something which fit her teaching career perfectly. She started out at Uganda Television, and she settled at Radio Uganda, where she became Head of Programming and Current Affairs at the time of her retrenchment.

Before you thought of becoming a lawyer, what did you dream of becoming as a child?

I thought I would be a journalist, an investigative journalist. I had dreams of owning my own paper long before Monitor and the Independent opened their doors. Everyone else said I would be a lawyer. However, there was also a time I thought I would be joining the army. It was something of an obsession of mine and impacted my attitude in secondary school. I had a glamorous view of what it was like, with stories from an uncle of mine, especially about things like military intelligence. That is where my passion was.

So, when was it you decided to study law?

I chose to study law mostly because there wasn’t an option for journalism as a private student. I wasn’t a big fan of the suits and formal lifestyle, but when I saw the options at my fingertips, law was what I went with. It was the pragmatic choice. When I finally finished University, I had a long sit-down with a friend, sadly dead now, who was serving in the army. We talked long and late into the night about career prospects in the army. However, the more he encouraged me to join, the more distant that prospect seemed to me. By the time I was tucking myself to sleep that night, the matter had been settled: I wasn’t going to join the army.

Were there any teachers, mentors, or early figures that inspired or pushed you toward the law?

I have been asked that before, and the answer that always comes to the front of my mind is Mrs. Gladys Wambuzi. In primary school, she gave us a homework assignment: to ask our parents what they wanted to be at our age. So I trundled home and asked my mum, who said she wanted to be a teacher – she was pretty sure of it. When I asked my dad, he was very philosophical in his response, talking about community and giving back to people, and I got lost. Eventually, he could see I was getting lost, so he simplified it and said: “When I was growing up, there was a man in the village, very clean, very organised, always wore white, and everyone looked up to him, and he was always tasked with organising things and guiding people. I wanted to be like that, and I found myself drawn towards teaching people, lecturing.” He asked me what I wanted to be, and I said that everyone thinks I should be a lawyer. His response was “Oh, a learned friend?” And that phrase stuck with me. I did my assignment, in which I declared I wanted to be a lawyer, a learned friend.

When I handed it in, it was the best assignment of the class, and Mrs. Wambuzi said to me, “I want you to conduct yourself like a lawyer, like a learned friend. Do you know what they do?”

I said I did, and that they fought for justice. I think that is when the earliest seed was planted. More often than not, when I got in trouble at school, it was because I was responding to a situation that I felt was unjust. This was true especially in secondary school, where the student leadership system in place left room for abuse. I know many who are still traumatised by this experience.

Walk us through your education journey.

I was in Kampala Primary School, followed by my eventful stint in King’s College Budo for my O Level education. Following events at this school, I did not return for my A Level education there and opted instead for Caltech Academy, an experience I am very grateful for. It gave me a better understanding of humanity. After that, I went to Makerere University and the Law Development Centre.

Did you continue your education after that?

Yes, and no. I did want to do a Master’s and so on, but just at the tail end of my LDC studies, my father died. I had a very sick mother, and thankfully, just one little brother still in school, so I unfortunately became head of the family. I had to start providing – I had to step up. That is when I joined Kalenge Bwanika Kimuli Company Advocates.

Describe your earliest experiences entering the legal profession.

Fantastic experience. I had the best bosses in the world. The best workmates were great, and the work was most fulfilling! I started my association with Kalenge Bwanika Kimuli Company Advocates when I was in my second year at the University. I saw them start out in the firm’s early years, liked what I saw and decided that this is where I would start and grow my career. So I hung around the firm and took up odd jobs to get noticed by the bosses. When I look back, I must have cut a rather odd figure because I sort of led a ‘rastaman’s lifestyle at the time. Anyhow, I jumped at the opportunity to undertake my clerkship term with the firm during my studies at LDC, and stayed on to work with them after completion of those studies. The firm was known for its skills in litigation; they were warriors, those guys. They were also handling a lot of receiverships and bank enforcement litigation, an area I took a keen interest in. When I left and joined up with my current partner at Ligomarc, we ended up in the same area of legal business. We expanded it, though, beyond litigation and advisory, and managed the enforcement ourselves. That is how we became the firm of receivers and secured lender rights specialists that we are known as, now.

How did you underline Ligomarc’s profile as a new practice entering the market?

We didn’t just take on managing corporate enforcement processes. You have to remember this was an emerging field, like AI is today, and we went all in. We examined how to turn these businesses around and got pretty creative in this regard. We realised there was an actual gap and set out to build the capacity to fill it. This area of Insolvency and Business Rescue is something no one studied at the time. And that is what I set out to study, but found challenges here too. There was no LLM and Master’s program in this space in any major university in the world. I later came across an organisation called INSOL International that had also identified this gap and started the Global Insolvency Practice Course to fill this space. INSOL is the world’s biggest body for bankruptcy and insolvency practitioners. They were responding to a gap that had become obvious after the 2007 – 2008 financial meltdown and were putting together processes that passed on the skills to respond to these situations, especially cross-border insolvencies. There was a need for a coordinated approach to insolvency and rescue processes of multi-jurisdictional entities in distress. Otherwise, the interventions would be worthless. So INSOL International got 12 or 13 universities from across the world to create a rich comparative curriculum for the course and got a number of jurisdictions to get their judges to sign on as course facilitators. It was a very practical initiative that I immediately signed up for. It validated what we were doing, enabled us to examine insolvency systems across jurisdictions from Canada to New Zealand, Brazil to Hong Kong, Cayman Islands, the British Virgin Islands, Côte d’Ivoire to Congo. Although the course is largely online, I attended classes in London, Dubai and Cape Town, and had a whole week of practical simulations to save a distressed multinational during which I appeared before the Bankruptcy Court of New York. The simulations also involved online court appearances before Insolvency Judges in Germany, New Zealand, etc. After an extremely short and intensive 9 months, I earned the designation of ‘INSOL Fellow’, eventually formally inducted as such in Sydney, Australia. Alongside all of that, the dream of my master’s and my PhD faded as I was furnishing a new capacity, one that strengthened our practice. Right now, I am deeply involved in insolvency work. Company restructuring, debt restructuring, value preservation and damage mitigation, that sort of thing.

What was it like, moving from Kalenge Bwanika Kimuli Advocates to your own practice, Ligomarc?

I was at Kalenge Bwanika Kimuli for 10 years – 4 years as a student and 6 years as an advocate. It was my home, and I actually intended to stay there. At Kalenge, I worked with a lady named Ruth Sebatindira, and we were heralded as the future of the firm. At some point, Ruth travelled to the United Kingdom to study a Master’s in International Taxation. We made a formidable team when she returned. We made a great team until she decided she was leaving for Deloitte. I was shocked that the bosses let her go. If we were the future, why were the bosses comfortable with her leaving? I started to question my role at the firm.

Tell us a bit about the evolution of Ligomarc – what gap was it addressing?

Sixmonths after she joined Deloitte, Ruth told me she was quitting to start Ligomarc. I wondered why she didn’t simply return. I was also at a crossroads of sorts. The firm had grown, but needed a fresh direction; however, the partners appeared satisfied with the status quo. I was receiving offers from various other firms. And then Ruth invited me to join Ligomarc. It was a difficult decision. Kalenge Bwanika Kimuli had nurtured me for 10 years. But I saw the potential of Ligomarc’s vision, and a year later, I joined Ligomarc. Ligomarc was meant to be a tax boutique, and the initial goal was to make use of our skill base in this regard. But when Ruth and I joined forces, the bank clients that we were serving at Kalenge started to come to us.

Their biggest concern was the speed and efficiency of their corporate recoveries. At the time, they had blunt tools like the police and court bailiffs. We saw a niche market where we could offer corporate recovery management services, and that is how we started offering insolvency solutions to the banks, beyond litigation. It went even beyond this, because these situations are inevitably toxic. When we manage recoveries, our approach is simple: let the bank client be part of the solution. How about we sell this together? Maybe you need some more time, but show me what you are going to do to turn the situation around. Arm me with something so I can go and tell the banks we are working on something. We have been able to turn around some businesses and sell assets with the creditor participating. As a result, we were able to save the bank money and avoid downstream litigation. We have a success record that speaks to about 84% of the cases we have handled, which is a pretty decent figure, if I may say so myself. What that figure means is that of the 10 cases we have handled in the last twenty-two years, we have failed to conclusively resolve only 2 to avoid full litigation. Such is the skill we have in resolving these sensitive issues without unnecessary toxicity. Furthermore, we hold a 50% success record for the case under litigation, testimony of the caution we employ in the decisions we make. That being said, we are confident that we will have a 100% record for these cases when they finally go through the appeal processes because we generally don’t have business defending indefensible cases.

Are there other firms offering these insolvency solutions?

Yes, there are other players in the marketplace now, but we are a market leader in this regard. But more interestingly, as a result of this involvement, we have a grasp of the need for capital. We have opened up an entity that caters to this. We have an investment fund that is out in the marketplace looking for investors that can fund or provide ‘patient’ capital to turn around distressed businesses that are viable. It’s a Fund Management entity named Rekindle Capital.

Do you ever have situations where the businesses you rescue or whose insolvencies you handle return to you and retain your legal services?

There are a couple of instances where the owner of these businesses comes back to us and says Look, I have a different venture. Many years ago, we handled a business in distress whose owners failed to adequately respond to our overtures for a joint resolution of their debt crisis. Initially, they took us to court, where their case faltered on a couple of preliminary issues, upon which they eventually left the country. A year or two later, their son-in-law called us from abroad to handle an urgent matter because he had failed to get a hold of his lawyer. According to him, his father and brother-in-law – the same family that had declined our overtures of peace – had encouraged him to reach out to us. Long story short, we started a very good friendship with this gentleman, and because of him, we ended up handling a number of interesting assignments in the infrastructure space. Another example is of a company that owns a highly mechanised farm in Northern Uganda, whose receivership we handled. We allowed the shareholders to reorganise themselves to redeem their company, helped them enter new arrangements with their numerous creditors, provided a mechanism for reinvestment in the company under the receivership because it was a viable business, and eventually guided the company and its secured lender in reaching new terms for the settlement of its loan obligations. That company is back on its feet, and we are currently its lawyers on retainer.

Which of Ligomarc’s speciality areas are you most passionate about?

That would be the Insolvency Services. When you are dealing with a debtor who eventually places his trust in you and permits himself to be vulnerable and open with you, compassion and empathy demand that you assist this person to wade through this extremely personal crisis. When I meet people like these, I find myself pouring myself into working with this debtor to find a solution that is more equitable to him or her. Of course, there are cases where I find difficult debtors, some clearly deluded with some sense of grandiosity or sense of entitlement, and then there are the fraudulent who think they can pay you off, etc.. These ones always fire me up differently. Now, there are cases I have come across where the lender is not just at fault but is being plainly unfair or unjust. I am not one to function well when I have little faith, in my case. My engine simply won’t ignite. So, in these cases, I simply decline instruction.

Is there any particular case, a landmark case or transaction that you remember with pride?

I think that would be the UDB restructure out of which came the famous Ojangole cases. It was just about injustice. A new board decided to restructure the institution and chose to stand with the person, the foot soldier who had unearthed and documented weaknesses in the Bank’s systems. That person was Patricia Ojangole. Those who stood to lose most from this decision decided to create a distraction, and the Inspectorate of Government, where they sought refuge, became the unthinking persecutor of a legitimate whistleblower. The IGG refused to listen to the Bank’s version of events and instead appeared obsessed with ensuring unquestioned compliance with its blindly issued orders. That obsession turned to rage when the Bank dared to speak up. War was inevitable, and the rest is history. I look back on that case with pride, knowing fully well that we fought on the right side of justice. What many people do not know is that when Ojangole was initially appointed Chief Internal Auditor of that Bank, the bank’s books had not been audited for about 10 years! And when an audit was finally done, it discovered a UGX 50BN heist that no one involved in that discrepancy has ever been prosecuted for. Instead, Patricia Ojangole, who led the efforts that had unearthed this, is the one who was dispatched to prison. I am proud justice was served. I look back on that case with pride because of the visible transformation we can all see at UDB. UDB would not be what it is today without the restructuring that occurred at that time, and I also think, without justice being served the way it was.

The other case that comes to mind is the restructuring of the Electricity Regulatory Authority and the overhaul of the electricity sector. As is normally the case, a new Board decided to realign the organisation by suspending some members of top management to pave the way for an investigation into their conduct. Our role was to guide the Board in the investigations and come to a fair finding. The issues we had to deal with here were quite complicated and rarely encountered in legal practice: formulas involved in the setting of electricity tariffs, costs and audits, dam construction, consumption of fuel, etc. We had to understand these things very quickly and apply them to the law. Thankfully, insolvency practice teaches you to adjust to these situations very quickly. Eventually, the report we helped author faulted the suspended officials, and my original fear that it would lead to a Court challenge never materialised. For me, this can only mean that the report was watertight. As an outcome of this assignment, we were retained by the client to guide in the strengthening of compliance requirements by licenses in the sector. Umeme, which was most affected by the tightening of these compliance requirements, decided to take on the regulator at the Electricity Tribunal and brought an array of expert witnesses from MIT, Canada, and whatnot. But because we had prepared well for these hearings, it didn’t fare too well for any of these experts, and the licensee soon saw the sense to enter a settlement with the regulator. It was about this time that we started to witness reductions in the electricity tariffs, better responses to power outages and other customer complaints, the rollout of Yaka, etc., etc. Umeme and ERA became centres of excellence and started to get international awards for the manner of execution of their respective mandates in Uganda. I feel proud that our services in this regard led to the provision of a better service for Ugandans.

Does Ligomarc offer any services to SMEs?

Yes, we do. Advisory services on structures and issues of that nature.We support start-ups in their formations – we are happy to waive fees. Offer complimentary filing and compliance services, tax advisory, that sort of thing – and when they grow, of course, they forget us. (Laughs)

How do you compare the practice of law back when you started with the situation today?

Of course, there are changes. The technology is different; the numbers are more: there are court premises, more judges, more lawyers, that sort of thing. But what really stands out for me is that there is significantly more specialisation. Today, if you have a criminal matter, you know who handles that. If there is a constitutional matter, you know who handles that. There are technology law firms. At Ligomarc, we define ourselves as a financial law firm. There is a firm that defines itself as a natural resources law firm, and they talk about minerals almost like a geologist does. There are law firms that specialise in procurement. This level of specialisation was not something you would come across when I was starting legal practice. Law firms no longer offer generalised services, and you will be seeing even more of this.

If you had the power to reform any aspect of the Ugandan legal system today, what would it be?

I would set up a 3-year project to deal with the case backlog in Ugandan courts. It needs that level of radical intervention. There are thousands of cases in the system, some filed as far back as the 1990s. The intervention would get lawyers and judges in their hundreds, create a special tribunal to expediently deal with this backlog, with a targeted timeline. We are going to need to sit down, put the resources aside, and finally remove this backlog.

You have served in significant leadership roles across different contexts (law, public service, traditional institutions). How did these roles shape your views on governance and regulatory frameworks in Uganda?

The culture of Ugandans in cutting corners is borne out of a failure to understand why systems and regulations exist.Governance is key for businesses to exist and thrive. People, for instance, fail to understand that paying your taxes improves your business since it requires systems for compliance, and systems are good for your business.

Once, I had to appear before a Magistrate in a case against the National Drug Authority, where someone was challenging the Authority’s refusal to issue a license. The Magistrate gave an injunction against the intended closure of a particular drug dispenser, so I asked: What do you know about drug regulation? There is a reason this Authority has not issued that license. These structures exist for a reason. So, as you cut corners next time, take time to see who has used that ‘panya’ and how well it ended for him. Then look at the others that have avoided it and try to see the difference. You will learn a lesson or two.

What is the role of lawyers in public service beyond litigation and transactions?

There’s a provision in the constitution that points out that the government shall provide a development plan for the country, and every other organ must align with this plan. It doesn’t matter what the government is. What lawyers need to understand is that we have a role in either participating in the improvement of that plan or in the implementation of that plan. Because if everyone starts doing things their way, the result is chaos. We have a role in national development; we have a role in organising society. Unfortunately for many lawyers, their work stops in the office. Do you advise your LC1 when he is punishing a petty criminal with corporal punishment, or do you look on in amusement? That sort of thing…

Do you have any mentors who influenced you significantly in your career?

Yes! My former bosses, Moses Kimuli, Chris Bwanika, and Stephen Kalenge – there can never be better mentors. They were patient with me, they understood my temperament, and they walked with me. I will forever be grateful. As a student, it was Professor John Ntambirweki – he kept me in line while at the University. If it wasn’t for him, I would probably be a soldier today.The kind of student I was, even at Makerere, there was a need for a one–man roll call, so I had a one-man roll call every day, courtesy of Professor Ntambirweki. Then, of course, there are my parents. The values I live today, they taught me first, and I saw them live them every day.

What are your thoughts on corruption within the judiciary system in Uganda?

I think I have to address this sweeping narrative that judges in Uganda are partisan and corrupt. If you were made a judge today, would that make you corrupt or partisan? Do you really think all the judges know all the parties that appear before them well enough to ask a bribe and become partisan in their judgment? Some of these are incredible individuals in their own right. It is a carefully curated qualification. The individuals, companies, or entities that may attempt to bribe a judge are already known. As are the judicial officials who may be bribed. But the vast majority of judges within the judiciary system are upstanding individuals. We should not let one or two bad apples define a system. It is an uninformed perspective and an unfortunate bias. We have some rotten apples, and we have some good apples. And the rotten apples are not very many. Our problem is that we have a culture of not celebrating good people.

How do you personally define ‘success’ at this stage of your life?

You cannot succeed alone. Success is how much opportunity you have created for yourself and other people.

How do you manage the question of work-life balance?

Not too well at the beginning. But I got better. You must make time for yourself. When I travel, I take time off for myself, soak in my surroundings, what people are wearing, the language, and the food. There was a time I was so engrossed in my work that I would not notice a beautiful day. Today, I use technology to lock out and make time for myself. When I am at home, my phone is set to DO NOT DISTURB. And it works. I also have a few quiet places I sometimes escape to for nature walks, swim, read a book, etc.

If you had to leave behind just one principle or one piece of advice for Uganda’s next generation of legal leaders, what would it be?

There’s something that the so-called New Radical Bar has exposed – a critical need for mentorship. Either there is a lack of available mentors, or young people do not accept the importance of mentorship. I would again borrow a quote from Game of Thrones: “If you want to lead someday, you must learn to follow.” For example, regarding the present situation at the Uganda Law Society, we knew where it would end. He, and you know who, may speak with bravado, but at the age of 50, he will look at this as a wasted opportunity. Experience is the best teacher, and you have the opportunity to learn from someone who has been there before. Find a mentor. The challenge may also be on us as senior lawyers – we need to learn to reach out. We need to make ourselves available for these young people because, as we can see, their disruptions affect us too.

Time to talk about your family…wife…children…

I have never been married…I hope to someday. I have one biological child, but I call myself a father of many. Ligomarc runs a scholarship program for several children, up to 40 of them. Our program runs in three schools: Mt. St. Mary’s College Namagunga, Mary Hill High School, and Kings College Budo. The schools pick the students, and we conduct background checks to ensure they meet our criteria. I say I am a father of many because I am responsible for this program at the office, which has enabled me to interact with many of these children and their parents. For some of these students, we have established a close relationship.

Finally, what message do you have for Uganda’s business community about the importance of sound legal practice and governance in national development?

If you are involved in business, find a lawyer you can trust. You need one. Many times, we are approached after the damage has been done. Also, be honest with your lawyer. If you are in business and you are in debt, find a trusted lawyer whom you can be vulnerable to to protect your assets. You should have the same relationship as you do with your doctor, with whom you carry out your annual medical check-up.

Looking at the future of corporate practice in Uganda, what worries you most about the business and legal environment?

Two things worry me. The first is technology and AI. I don’t think we have understood the full extent that the advancements in this space have for us in future. For example, we are signing on new applications, giving away our data to people behind corporate veils every day. Spotify, Apple, Google, Netflix, etc. Where will all this information about me end up? How will disputes be resolved? How does one fight Netflix or Apple in a fair and even match? Who will superintend over these fights? Consider how disadvantaged we already are as Africans, and think about what the future for us will actually be as opposed to what it looks like. This uncertainty unsettles me mainly because this trend is inevitable, and few people seem to lend gravitas to the subject to paint an accurate picture for me to assure us of a fairer world for our people. There are a number of people who claim to know, but I get the sense that they are simply parroting what they have read or been told.

The second issue that worries me is the quality of the lawyers we are producing today. Undoubtedly, many are extremely smart, and it’s not their intellectual capacity that worries me. My point is that young lawyers have come to the profession with unreasonable expectations. I don’t know whether it’s the numbers being churned out every day that are overwhelming the system, but we senior lawyers appear unable to do our part to mentor these young people. The result is that many are wading through the ranks and growing without becoming ripe. Because of this, for instance, young litigants will lose a case, then insult the presiding judges and blame everyone else instead of looking to themselves to learn from the experience. This inability to introspect, learn and grow is really worrying.

Where do you see the greatest opportunities for growth—for law firms, for businesses, and for the broader economy?

I could point to specialisation, but that is something that has been going on for a while now, and that I mentioned earlier. What I would like to emphasise, though, is the need to broaden our horizons as lawyers, and the fact that that is where the greatest growth opportunities will be. A lot of law firms in Uganda, after one contract, lock it down as a retainer and relax. You can actually position yourself in a continental market, or even a global one. The developed world, for example, your typical muzungu, views the African continent as an untapped resource, as open ground. I have had instances where a potential client approaches you and says: I have a problem in Mali. Can you handle that? And I will say yes, tell me about it. And I will find a lawyer in Mali, we will crack that case together (using his familiarity with the legal landscape and my technical strengths and expertise) and share legal fees. Business partnerships to tackle the continent offer unique opportunities currently just beyond our scope. It’s an attitude thing that we, Ugandan lawyers, need to adopt to expand our horizons.

We can also consider setting up offices outside the country. Think of a lawyer who sets up offices in Dubai. You are probably thinking that would be to target oil sheikhs and the like. However, there’s a sizeable Ugandan community in Dubai, and a lot of businessmen here do business with Dubai. Alongside this, we also export a sizeable contingent of labour to Dubai. These categories of people will need legal services, and often pay top dollar to law firms located in Dubai. Don’t look at the individual, look at the market, and find a product for them.

I have seen one or two engineering firms do things like that.

Business Development is critical to law firms. Look at markets, not borders. Alongside this, invest in yourself as a law firm, in your specialisation. I find Ugandans to be brilliant people. And when given an opportunity, they do it well. So if they redefined themselves and their perspective, they can take advantage of Africa as an open ground. It is the last frontier for big projects, and the opportunities for business are immense.

Tapping into areas like intellectual property and copyright are areas for growth. Ideated areas, and we have a young population, one that needs people to monetise these ideas. Who helps them in this regard? Lawyers!

There are more fields lawyers can examine and specialise in. Human Resources is one. Procurement is another. These are fields that involve managing contracts, deliverables and performance. Again, this is an area particularly suited to lawyers and is a specialisation where there is room for growth.

Then there are areas that have not been touched at all, like medicine. Targeting the Ugandan medical community in the diaspora, for instance, in South Africa, is a business opportunity for lawyers in Uganda to grow into.

Finally, I should mention this. The future will require lawyers to be multidisciplinary because of how specialised the sector is getting. You are not going to be a capable financial lawyer without shedding your fear of numbers and getting a grasp of mathematical and accounting principles.,

How will global trends (technology, cross-border transactions, ESG) shape the practice of insolvency law in Uganda? And in addition to this, how well developed is our insolvency law?

We are actually leaders in this regard, which might surprise you…

Doesn’t surprise me. According to the Global Entrepreneurial Monitor and the World Bank, Uganda is considered the most entrepreneurial country in the world.

While our insolvency law is one of the more vibrant ones on the continent, we have yet to get the word out within our business sector. This is particularly true at a cultural level. We can impact this at the training level, the training we do in law school, where it is an optional subject, and even then, about two modules are utilised. The mindset of productive insolvency is to give a company a chance, and yet this hasn’t been the case. At LDC, it was referred to as ‘Liquidation’…we have managed to impact that…

The nomenclature impacts the attitude of course…

Absolutely. This also includes some of the judges coming up to speed with insolvency solutions, and not simply sticking to the straightjacketed options that have typically defined the sub-sector. Modern solutions in this regard adopt creativity, and yet sometimes the judges struggle to adopt this.

Another thing to consider is that these distressed businesses, as part of the insolvency process, often need financing. I see this as an investment opportunity for money lenders, especially if they formalise themselves. This is what a fund like Rekindle Capital, which is affiliated with Ligomarc, is set up for.

If you were addressing a class of first-year law students today, what would you tell them about the realities of legal practice—what they need to start learning and preparing for right now?

I am sure the attitudes of first–year law students have never changed. They need to understand that the options out in the real world are infinite. None of the cliché first steps, like lining up a law firm where you first do an internship and then join after getting your practising certificate, or lining up for a job at an NGO. There are several new specialities opening up, as I earlier mentioned, new areas like HR and Procurement. Medical Law is untouched. You can be a specialist in Nuclear Law, and you can get involved in the legislation surrounding it. Intellectual Property covers an incredibly wide area and is getting increasingly important. Don’t just wait to join your uncle’s law firm because it has been in existence forever.

The other thing I would highlight to them is that ours is a counselling profession. That is where the title ‘Counsel’ is derived from. The problem with our training is that we are not trained to counsel. Our legal education trains us to identify legal issues. It is often lost to us that clients come to us with serious legal problems. The culture is to think of money first. We should help the client navigate a route around his problem. To do that well, we must somehow learn how to counsel. At a personal level, for instance, I was traumatised by the first divorce case I handled. Hearing from my client about how her husband meted out violence at will made handling the negotiations with him and opposing counsel a chore. I had emotionally invested myself in the case, and counsellors don’t do that. They are trained not to.

Alongside all of this, we meet all kinds of characters in our work: liars, manipulators, the corrupt, that sort of thing. As a result, we need to understand people. So, alongside my previous point, I would encourage them to take on a course that facilitates this as well, something in psychology. Our work requires that you understand mindsets, the mindset of the victim, and of the perpetrator or the aggressor, and navigate a way around this. Learn about personalities and how to deal with them.

Beyond the classroom, what practical skills and attitudes should young lawyers develop early to thrive in this profession?

That’s another good question. There’s he hard stuff you learn at school; then there’s the soft stuff, what you learn from your family, friends, the people around you in social interactions. Communication skills, the ability to listen – listening skills. I have been in situations where I am making the same point as the other person, and he is still not listening. Time management, the ability to develop grit in the face of adversity, and the ability to recognise that there is unfairness in the world. I would push for them to engage in sports and play games. It teaches you the importance of working within a team to achieve the same objective, and also helps with other soft skills.

I would also get them to understand that the journey has barely begun. Young lawyers feel like they have got it made after completing LDC and getting their practising certificate. I would drum this into them – it is an attitude they should be desperate to lose. Start at the lowest rung, endear yourself to the bosses, be around for the midnight candle meetings and strategy sessions, because that is when you learn.

What common pitfalls or misconceptions should both students and young lawyers avoid as they embark on their legal careers?

Peer pressure really has a detrimental impact on them. Lawyers and money, and reaching for fancy lifestyles (shakes head). If you have to stay in Nansana, brace yourself – you will move to the fancier neighbourhoods when you have earned it. The flashy cars need to be earned as well. And cutting corners is another pitfall they struggle with.

Also, be intentional about the firm you choose to join, or attempt to join. This is going to impact your midterm and long-term future, and is something you should put some thought into.

How important is mentorship in shaping a successful legal career, and what advice would you give young lawyers on finding and working with mentors?

You are likely to adopt the style and the habits of your mentor, so you have to be careful about it. The mentorship process empowers the mentee; he can hire or fire, so to speak, his mentor. You are the one who makes the time to see the mentor. I don’t think they ever see it that way, but it’s true. The things to consider when choosing a mentor are his or her professional standing, his or her ethics or values, and personal values and where that relationship will take you. You choose wrongly and you are likely to suffer for it.

If you could speak directly to both law lecturers and their students, what would you urge them to focus on so graduates are better prepared for the evolving demands of practice, particularly in insolvency and corporate restructuring?

Insolvency and company restructuring are high-pressure fields. A restructure, for instance, involves a lot of emotional turmoil and pressure, whether it is from employees or external, from family, suppliers, society, that sort of thing. These two fields are a specialisation of company law. They are just not taught well enough. There is not as much emphasis given to it, even though it is that far-reaching.

More importantly, it is pretty prevalent and is part of the human experience. Who hasn’t suffered financial glitches? Who hasn’t decided to stop drinking, go on a diet, or do things of that sort? So, company restructuring is simply part of the human experience, another thing that should be emphasised. And while it is far-reaching, it has far-reaching implications, and this is also not emphasised at the undergraduate level.

Another aspect is that insolvency and restructuring are about numbers, and often, lawyers come into the game without adequate grounding in this regard. The training must include an emphasis on numbers, on financial proficiency, an area that lawyers often avoid.

Finally, insolvency and company restructuring require a certain level of creativity, of thinking outside the box. Unfortunately, many lawyers are straightjacketed, and this is a result of their training, which promotes a risk-averse approach. In fact, some judges will punish insolvency lawyers for being creative in this regard, for just trying something new and outside the box.

Vivo Puts Two Downtown Kampala Shell Stations up for Sale Amid Congestion Concerns

Vivo Puts Two Downtown Kampala Shell Stations up for Sale Amid Congestion Concerns