When the authority responsible for procurement and disposal of public assets falters in its duties, the impact doesn’t just stay within its walls – it ripples dangerously through the economy, governance structures, and public trust.

Procurement is the engine room of public service delivery, powering everything from roads and hospitals, schools, and critical infrastructure.

The crack in compliance

So when oversight breaks down, mismanagement, corruption, inflated costs, and outright theft aren’t far behind.

Without rigorous inspection and monitoring, procurement processes become a fertile ground for collusion between suppliers and government officials.

Why? Because contracts start getting awarded not on merit or value-for-money, but on handshakes or kickbacks

The result? Shoddy goods, subpar services, and a playing field tilted against capable, reputable firms.

The whole integrity of public procurement begins to crumble.

But it doesn’t end there. Service delivery delays become the norm. Investor confidence cracks and infrastructure stalls.

Slowly but surely, government’s ability to meet its citizens’ needs wears thin.

Even more troubling is the stealthy loss of public wealth when asset disposal is loosely monitored.

Government vehicles, land, and machinery can mysteriously find themselves in private hands, at what can only be called “friendly” prices.

It’s a quiet haemorrhage of public wealth, often with a whisper of backdoor dealings.

And this isn’t hypothetical – there’s a paper trail.

A government audit of the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets Authority (PPDA) uncovered significant lapses in the execution of its mandate during the 2023/24 financial year.

Despite having a solid strategic work plan, PPDA dropped the ball in several critical areas.

Three functions, in particular, stood out for their underperformance: oversight of procurement systems, harmonisation of procurement policies and laws, and capacity-building for procurement professionals.

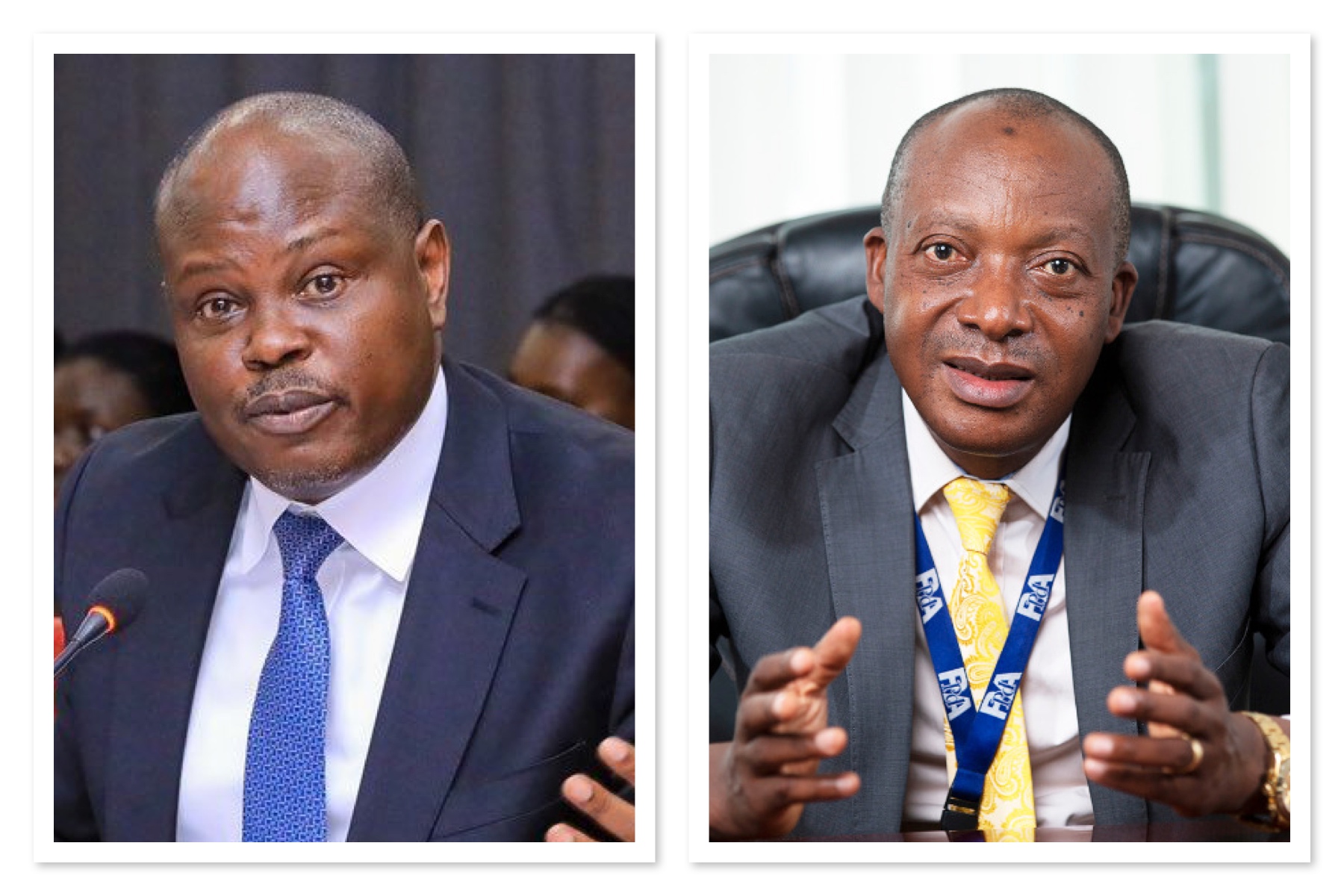

165 audits were carried out – but according to Auditor General Edward Akol, that was just a drop in the ocean compared to the scale of public procurement activity.

The audit found that reforms were mostly reactive, triggered by complaints, not led by a forward-looking strategy, while training programmes were limited to occasional forums, far from the kind of sustained capacity-building the sector needs.

These gaps point to something deeper—a worrying lack of prioritisation.

Akol put it plainly: some mandated activities were “not prioritized.”

Whether that is due to tight budgets, internal inertia, or leadership gaps, the outcome is the same—a regulator falling short of its responsibilities.

And when oversight is weak, irregularities thrive, and when standards become inconsistent, capable suppliers walk away, and that means public funds evaporate with little to show for them.

The pursuit of value-for-money also risks becoming more aspiration than reality.

“I advised the Accounting Officer to ensure they align the planned activities with the mandate of the Authority,” Akol noted in his audit report.

But as any seasoned bureaucrat knows, even the best plans need fuel – money, and the will to spend it wisely.

Budget vs reality

The Public Finance Management Act requires public accounting officers to present appropriation accounts comparing actual expenditures against budget allocations.

This helps ensure transparency and accountability for every shilling spent.

In PPDA’s case, it was allocated UGX24.111b for the year, with UGX23.895 billion released, showing a 99.1 percent performance rate. Not bad at all.

But of the UGX23.895 billion 66.4 percent went to wages, followed by non-wage and development expenditures, with only minor shortfalls.

That UGX0.215 billion shortfall (a modest 0.9 percent of the budget) affected administrative and support services under governance and security and anti-corruption and accountability programmes.

And when you look deeper, things get murky.

Despite no funding, some of these activities were marked “achieved” in PPDA’s quarter four performance report, suggesting that something is off in the reporting.

Were these achievements the result of creative reallocations? Efficiency gains? Or perhaps just…optimistic reporting?

Whatever the explanation, it raises questions about how closely financial inputs are tied to actual outcomes – questions that matter when public trust is at stake.

Akol believes these unfunded activities reflect a failure to deliver the full range of expected services.

Even if the sums were small and didn’t hit core mandates, the principle remains: transparency and full implementation matter.

The accounting officer – Benson Turamye – on his part, acknowledged the shortfall but said these were just overheads, after all, committing that PPDA would, in future, work with Ministry of Finance to secure full releases.

PPDA scored high on overall budget execution. But those unimplemented activities-even minor ones-hint at underlying issues in prioritization, planning, and reporting.

“I … urged the Accounting Officer to ensure accurate performance reporting rather than misreporting issues as exhibited by indicating that all targets were met, yet it was to the contrary,” Akol notes in the audit report.

His audit reveals that of the UGX23.895 billion released, UGX23.889 billion was spent, leaving UGX6.16 million unspent.

It’s a small sum – about 0.03% of the total budget – but even a shilling left unused represents a service undelivered or a target unmet.

The leftovers were earmarked for non-residential building improvements (UGX5.16 million) and postage and courier services (UGX1 million). Neither was implemented fully – another red flag.

These might seem like footnotes in a national budget, but they are still part of a legally approved work plan.

Akol further notes that this could reflect a lack of commitment or a shift in priorities, either of which should have been formally communicated.

PPDA said the money was meant for building improvements, but was unused. No further justification was provided.

Audit trail

An assessment of how it used its funds last financial year on whether the activities it was supposed to support were actually implemented shows a generally satisfactory performance.

The audit zeroed in on three key outputs comprising 25 activities, collectively valued at UGX22.9 billion.

Of these, two outputs – covering 21 activities and accounting for UGX21.6 billion – were fully implemented. That’s a solid execution score and signals a strong alignment with the approved budget.

The third output, involving four activities worth UGX1.3 billion, was only partially implemented.

Three of the four were fully completed, but one – the inspection and monitoring of Procuring and Disposing Entity (PDE) processes – was only partially executed.

The Auditor General noted that this shortfall might stem from a lack of prioritization or perhaps a case of waning commitment.

Importantly, there were no outputs that were completely abandoned, which is a positive indicator of follow-through.

Still, even partial execution – especially when it involves oversight – can blunt institutional effectiveness.

But failing on procurement inspections suggests a missed checkbox – a crack in the compliance wall – on which transparency, value for money, and due process depend.

PPDA, however, notes that not all activities require direct funding, as some are handled using internal resources.

But that explanation doesn’t quite explain why a key, funded activity like procurement monitoring fell short. Internal resources or not, this is core business.

So, while the overall implementation rate deserves a nod, any lag in governance-critical functions like monitoring demands sharper planning, tighter prioritization, and a stronger grip on accountability. These are the gears that keep the machine running smoothly.

“I advised the Accounting Officer to exhibit transparency and disclosure in management process by providing all required budget information and related activities – and to ensure full accountability for the funds provided,” Akol noted.

Disposal dilemma

The PPDA has already raised alarm over what it describes as glaring flaws in the government’s public asset disposal process – flaws it says are at the heart of most bidder complaints.

Early last month PPDA Registrar Mansoor Atiku Saki asked government to urgently revisit and reform the asset disposal procedures, noting they were the leading source of disputes.

“Government needs to step in and clean up the disposal process to ensure the public has priority participation transparently,” he said, noting that a significant number of complaints stem from allegations that evaluation committees tamper with criteria during the disposal process, undermining fairness and transparency.

“When entities invite bids, they initially disclose the evaluation criteria. But along the way, some committees alter those criteria to deliberately lock out certain bidders,” he explained.

One of the PPDA’s major concerns is the overly restrictive nature of bid requirements, which Saki noted that in some cases, bid conditions appear tailor-made to favour a single party, effectively shutting out fair competition.

Another issue is the lack of transparency in bidder notifications.

“The notice of the best evaluated bidder is often not publicly displayed, so unsuccessful bidders are left in the dark about why they lost out,” he said.

Compounding the problem is the limited access the tribunal has to the Electronic Government Procurement (EGP) system – the digital platform where procurement processes are conducted.

This lack of access makes it difficult for the tribunal to investigate and follow up on complaints promptly.

“When a complaint is lodged, the tribunal often struggles to get the necessary documentation because it’s not integrated into the EGP system,” Saki said. “That delay undermines the tribunal’s ability to ensure fairness.”

As the complaints pile up, PPDA is pushing for reform, urging government to prioritize transparency, revise restrictive criteria, and provide the tribunal full access to procurement data to safeguard the integrity of public asset disposal.

Ruparelia Foundation to Hold Free Eye Camp in Bukedea in Honour of Rajiv Ruparelia

Ruparelia Foundation to Hold Free Eye Camp in Bukedea in Honour of Rajiv Ruparelia