Dr. Catherine Kibirige’s parents were some of the most accomplished Ugandans in post-independence Uganda. Her mother, Dr. Rebecca Nyonyintono, received a partial bursary to go to Gayaza High School. She went on to Makerere University and then received a Carnegie Foundation grant to study for her PhD in Sociology from the State University of New York in Buffalo. Dr. Nyonyintono was one of the first Ugandan women to receive a Ph.D. Catherine’s father, Mr Samuel Kibirige, went to Kings College Budo and then got a first-class, Summa Cum Laude, degree in Electrical and Electronic Engineering at Swansea, University of Wales in the United Kingdom in 1969. He was awarded the Institution of Electrical Engineering Prize for excellence.

But her life started in exile. Using their academic accomplishments, Catherine’s parents wanted to remain in Uganda and build the nation. However, her paternal family’s involvement in politics rubbed the Idi Amin regime the wrong way, and two family members vanished under suspicious circumstances. This prompted the family to flee to Nairobi, Kenya where Catherine and her sister Agnes, were born and raised.

Growing up, Catherine was drawn to science due to the AIDS scourge that affected Uganda in the 80s. “Science was my strongest subject, but I leaned towards Chemistry, not Biology, by the time I got my A Levels in the UK. I wanted to do something in research about the AIDS scourge but I didn’t get into medical school because I struggled with Math.” This did not stop Catherine however, as she went on to work in HIV research anyway.

After completing her Masters at the University of Bath in 1999, Catherine moved back to Uganda to rest for a while after suffering a bout of sickness. But within three months, she was getting bored and started seeking employment. Her first stop was Makerere University. “My mother was working at Makerere University and the head of her department, Professor Edward Kirumira, knew Professor Nelson Ssewankambo, the Dean of the School of Medicine at the time. He passed on my CV and arranged an introduction for us and I was able to interview for a volunteer internship. I ended up working at the Uganda Virus Research Institute in Entebbe as part of the Rakai Health Sciences Program from 1999 to 2003”.

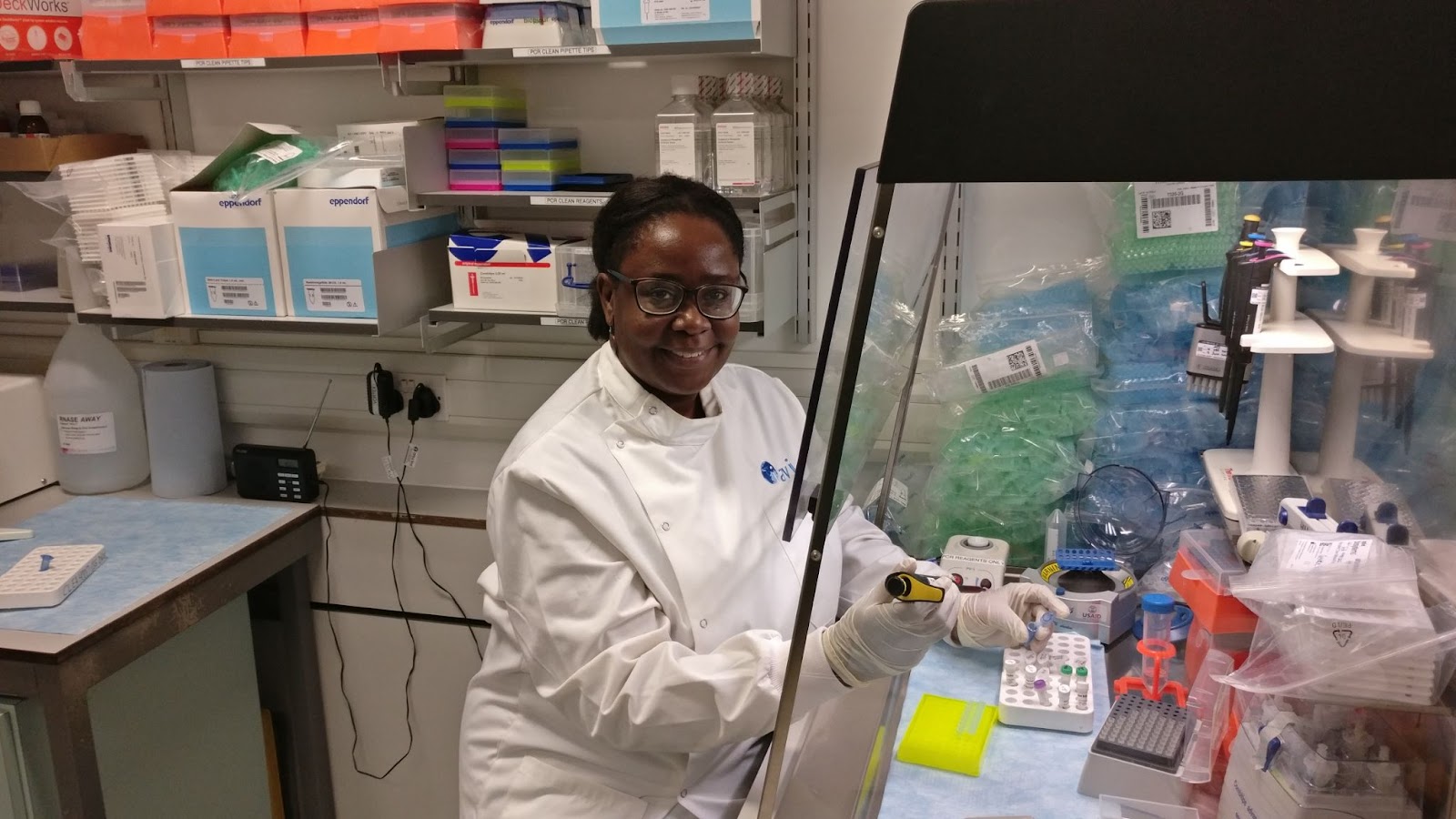

“I started working in Rakai on AIDS research, which was a dream come true for me. The Rakai Health Sciences program was collaborating with the US Military’s HIV Research program at the time, so this is how Dr. Kibirige was initially recruited to work on a US Military project. “At that time, they were sending samples to the USA for viral load testing as part of their research, but it was logical to build the capacity for that locally, so my initial project was to help with the transfer of the viral load testing to the Ugandan laboratory.”

The Rakai project was also collaborating with Johns Hopkins University and through a twist of circumstances, Catherine got an opportunity to study at Johns Hopkins University as a graduate scholar, but she had no idea how big of a deal it was to begin with. “I wasn’t too intimidated when I went for my interview, simply because I didn’t fully understand how competitive or prestigious the institution was. Looking back, and knowing what I know now, Ignorance gave me the gift of bliss. I would not have dared to apply otherwise. I would have been too nervous.” With HIV wreaking havoc then, Johns Hopkins was one of the centres at the forefront of the research on how to combat the virus.

“I had a chance to work with Dr. Joseph Marglick who had been involved in studying the epidemic right from when the first cases of HIV broke out in the USA. He was doing his PhD in San Francisco and has therefore been involved in the initial characterization of the virus and in determining the original treatment regimens for the disease. It was a real honour and privilege to be able to work with him.

As fate would have it, Catherine’s first job after completing her PhD was another position with the US Military through the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. “I had decided that I wanted to do work that could be translated more directly to patient care. I was initially recruited to work on a Nigerian-based project but there were several delays. While I waited for this project to start, an issue arose with an HIV test the military was using to study samples from its HIV Vaccine trial in Thailand. I was working in the Diagnostics Division, in a technology assessment laboratory, so the test was brought to our laboratory to investigate. This ended up becoming my project for the rest of my time there and is the basis of the HIV tests I am developing now. The initial experiments were done during this time.”

Catherine currently holds many titles. She is a Senior Research Associate at Imperial College London’s Center for Immunology and Vaccinology as well as the chair of the board of Trustees for the Center for Research and International Development (CENRID) in London, England. She is also the Founder and Entrepreneurial Lead for the “HIVQuant Project”.

The HIVQuant Project’s ultimate mission is to make HIV treatment monitoring and early infant diagnosis more accessible in resource-constrained settings. Catherine is doing this by developing ambient-temperature research and diagnostics kits that do not require refrigeration and have prolonged shelf lives. She is also developing simplified protocols and optimising them to work on a portable, car battery or solar-powered instrument so that the kits can be used more widely, including in rural hospitals or clinics that do not have reliable electricity, sophisticated equipment or specially trained staff. She explains the pain points behind this project.

“People living with HIV have to routinely take viral load tests or measure the levels of the virus in their blood to monitor if their treatment is still working. If the virus is undetectable, this means it is untransmittable or they cannot spread the virus to others. In the absence of a vaccine or cure, this is the key mechanism we have to control the pandemic. Currently, for treatment monitoring in Africa, blood is drawn from the patients at specific district-level hospitals and sent to a central laboratory in the capital city for the viral load test.”

She adds, “The results then become available online in a month or two, but it typically takes 3 months or more for the results to get back to those in rural areas. The system is very inefficient and is contributing to a surge in drug-resistance development in Africa because some people do not adhere well to the drugs and we are not catching this early enough and switching them to alternative therapies. It is causing an increased spread of drug-resistant strains of the virus and preventing us from really combating the pandemic”.

Catherine’s kit, protocol and system will help to curb these inefficiencies. The assay has various formats, including an ultra-sensitive format that can be used for cure research. Catherine hopes that this will make participation in cure research more possible for people living with HIV in Africa as well. Catherine has secured various innovation funding awards in the UK. These include a “Wings for Ideas” award from Imperial College, a UK MedTech Accelerator Award and an Impact Accelerator award through the UK government’s Research and Innovation scheme.

She was able to build a prototype and last month flew from the UK to Malawi to begin tests. She has built a notable team of researchers to help her achieve this mission. They are putting together a business plan to transition from a project into, possibly a non-profit venture initially then a for-profit business. They hope to be officially set up by the end of the year. Watch this space for a Ugandan, Female-led entrepreneurial project that is contributing towards the fight against HIV.

This story was published in a partnership with ORION, a community of ambitious Founders, Fund Managers and Career Professionals in Uganda and of Ugandan descent. Dr Catherine Kibirige is an ORION Member.