On September 4, 2025, Justice Susan Odongo of the Commercial Court Division of the High Court in Kampala ruled against an application by the Baitwa brothers and their company to set aside a garnishee order. The order froze accounts of Three Ways Shipping Services (Group) in Stanbic and Standard Chartered, clearing the path for recovery of a $126,000 debt owed to Kenyan firm Transpares. The Baitwa brothers, Geoffrey Baitwa Bihamaiso and Oscar Rolands Baitwa Businge, had argued that they and their Ugandan group company were distinct from the Kenyan subsidiary that incurred the debt. But Justice Odongo dismissed this defence,…

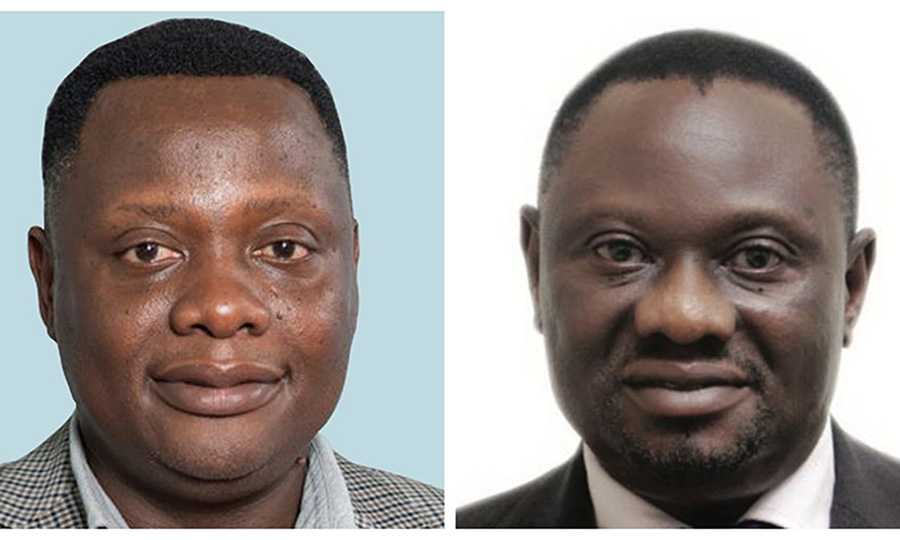

Three Ways Shipping: The Baitwa Brothers’ Riotous Decade of Court Battles and Their Bid for Reorganisation The Baitwa brothers, Geoffrey Baitwa Bihamaiso and Oscar Rolands Baitwa Businge, have had a tumultuous court history, and even when they have won some cases, they have left indelible marks on their reputation. But the brothers are now on the road seeking to recover from the past. In 2023, they unveiled Bro-Group, a holding company designed to consolidate subsidiaries and attract new investment.

The Baitwa brothers, Geoffrey Baitwa Bihamaiso and Oscar Rolands Baitwa Businge, are now on the road seeking to recover from a riotous past that has been characterized by multiple court battles.